A Brief History of Black Names

- Dec 22, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Dec 26, 2025

When I say Keesha and I say Hannah, what pops up in your head? How many Black girls named Molly or Becky do you know? What about Deja or Kiara? Why are so many Black American names so distinct and unique? Are Black names "ghetto"? Keep scrolling for a brief history of Black Names.

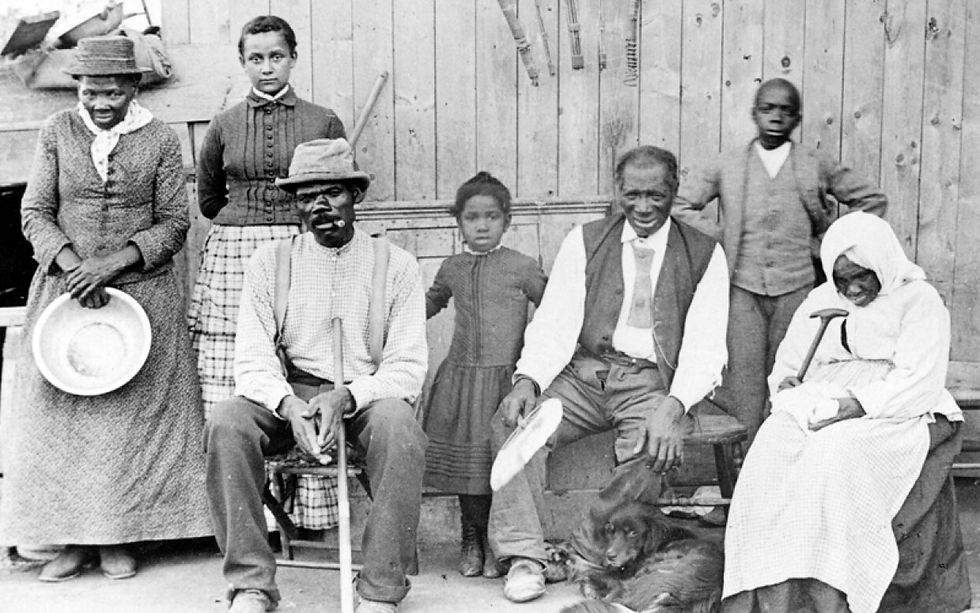

White enslavers gave enslaved Africans new names

By many estimates, approximately 30-40% of the kidnapped people from Africa were muslim, meaning they likely had Arabic names. Those who were neither Muslim nor Christian had their own significant names from their own cultures. When brought to America, the earliest enslaved people tried to keep their original or “country” names, but one of the simplest ways to dehumanize them and trample their spirits was by taking their names and giving them new ones

During the colonial era, classical names like Virgil, Hannibal, Titus, Hercules, Phoebe, Venus, and Daphne were given to the enslaved. These were not routine names for white people, and noted art historian Susan Wegner, “Classical names could show off slave-holders’ learning while also mocking those humans held as property by giving them ironic names of powerful ancient rulers, gods, and heroes.” Venus was an especially popular name bestowed on Black women, and stemmed from a word meaning “physical desire and sexual appetite.” Its was also, of course, the name for the Roman goddess of love and her Greek equivalent, Aphrodite.

According to cultural anthropologist Sarah Abel, this “reflected and licensed the lasciviousness of European slaveowners toward African women, making such behaviors ‘sound agreeable.’” As the years passed and the era of the Great Awakening peaked, enslaved people were given increasingly European and Christian names like Elijah and Moses. As with much of slavery, the conditions that people lived under varied by the enslaver. Some enslaved people were allowed to pick the names of their children and others weren’t.

Freedom Sometimes Meant a New Name

As Black people won their freedom with blood, sweat, and tears by running away and becoming abolitionists, many changed their names to break away from their enslavers. Araminta Ross, referred to as “Minty” in runaway notices, became Harriet Tubman, taking the last name of her husband John during a time when enslaved marriages were not recognized. Isabella Bomfree became Sojourner Truth. In 1838, escapee Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey had long dropped his two middle names already, and been known as Frederick Stanley and Johnson, but in New Bedford there were already too many Johnsons. Turning to the abolitionist he was staying with, ”I gave [him] the privilege of choosing me a name, but told him he must not take from me the name of 'Frederick.' I must hold on to that, to preserve a sense of my identity." Douglass was pulled from a Scottish poem.

Still, during and after slavery, some Black people took their former master’s surnames, or gave their children names inspired by American ‘heroes’ like George Washington, Ben Franklin, and Abe Lincoln. But also, the 1880 census showed that 1/4 of Black homes had a son named after their father.

Distinctly Black Names Have Long Been a Phenomenon

What were the most common first names for Black people by the early 1900s that were barely used by white Americans? Abraham, Alonzo, Percy, Perlie, Prince, Israel, Isaiah, Presley, Purcelle, and Titus. According to The Ohio State University’s Trevon Logan— GO BUCKS!— these kinds of names had long been popular among the Black population, with these names also listed commonly between 1719 and 1820 on ship manifests. In fact, 3% of enslaved people had names that were considered specifically Black because white people didn’t use them, and this percentage would hold steady in the 1920s.

As the 20th century went on, popular names for Black men with specific European origins include Jermaine— of French and Latin, Darnell— of the Anglo-Saxon, Tyrone— of the Irish, and Leroy— of the Normans. Sociologist Newbell Niles Puckett, author of Folk Beliefs of The Southern Negro, collected thousands of distinct Black names from 1619 to the 1940s in 1975’s posthumous Black Names in America. With a name like Newbell Niles Puckett, he was destined for the job— and he even created a list of unique names, which you can access here.

The Civil Rights & Black Power Movement Impacted Names

In case you’re discounting the importance of Black people’s autonomy over their own names, consider Cassius Marcellus Clay becoming a muslim man named Muhammad Ali. He was named after his father, who had been named after a Kentucky abolitionist and politician. Numerous white and black people objected to the name change and refused to refer to him as Muhammad Ali. "What's my name, Uncle Tom ... what's my name?” Ali taunted one opponent between punches who still called him Clay. Ali’s success, confidence, and religion— which would become contentious when he refused to be drafted for the Vietnam War— made him a pariah in the 1960s as much as the name change.

He was derided as cocky and arrogant and people intentionally used Cassius Clay to strip him of his autonomy and achievements. In the months of promotion for 1971’s The Fight of The Century, Joe Frazier, a pro-war boxer, referred to Ali as Clay, which prompted Ali to call him an Uncle Tom and race traitor. He said, “Why does he insist on calling me Cassius Clay when even the worst of the white enemies recognize me as Muhammad Ali?” By the way, these men had beef basically for life, especially because Frazier beat him in the fight and Ali reneged on his promise to crawl across the ring and call Frazier “the greatest.”

So Ali’s name change was one of the most visible and debated ones, but in the late 60s and 70s, lots of Black people in the wake of Afrocentrism and the civil rights and Black power movements, were changing their names. Malcolm Little had become Malcolm X and Malcolm Shabazz back in the 40s and 50s, respectively. Black Panther and future bestselling musician Yvette Marie Stevens became Chaka Kahn when she was 13, after the name was bestowed upon her by a Yoruba priest. Stokley Carmichael became Kwame Ture, though he went by both names by the end of his life. Future politician Frizzell Gerard Tate became Kweisi Mfume. Kareem Abdul Jabbar, who was born Lew Alcindor, publicly began using his new name in 1971 after he converted to Islam, like Muhammad.

Black Girl Names Are Super Unique

By 1977, the average Black female got a name that was 20 times more likely to be given to Black girls than white ones. Popular ones included Aaliyah, Assata, and Afeni. Names with -La— like LaShonda and LaKeisha, became common from this period too. In the early 90s, there was news coverage on unique black names, as the Sha-prefix became popular with names like Shameeka and Shaniqua. For boys, there were Quantaviuses and Ladariuses. Complained a Florida college professor to the Tampa Bay Times in 1993, "It's a class thing. . . . The middle class doesn't have a need to bless their child with such names. Younger teenage girls are trying to make their child unique. . . . She wants her to be unique so she gives her a name the child can't spell until she is 13, and nobody can pronounce.”

Agreed a columnist, "They are prevalent in the ghetto...If giving yourself an African-sounding name is supposed to inspire pride . . . we certainly know enough Black kids with exotic-sounding names who are part of the crime statistics. I think that I can overcome the stereotype of a name if you get to know me. But we are not always given a fair shot. A Muslim name after the bombing of the (World) Trade Center is certainly not a plus.” Warned University of Florida’s Black Studies’ director Dr William Simmons, "Blacks will go further back with those kinds of names.” Perhaps as a form of backlash, there was a small bump in the number of Black people choosing distinctly white names in the late 1990s and 2000s. But creative names— particularly for Black girls, were and are a continuing trend. In 2004, Roland G Fryer and Steven D. Levitt found that in California alone, “nearly 1/3 of African American girls are given a name given to nobody else in the state.” They found that having a creative name was only more likely to make a Black woman give her own children creative names.

Beyonce's Unique Name

Miss Tina, born Celestine, christened Bey after her own maiden French Creole name, Beyonce. Ms Tina’s surname was misspelled on the birth certificate by the nurse, making hers different from her siblings whose surname was Beyince. Ms Tina explained to Elle that she asked her mother, "Why didn't you argue and make them correct it?" and she said she did the first time and was told, "Be happy that you're getting a birth certificate because at one time Black people didn't get birth certificates... because it meant that you really didn't exist and you weren't important." And that’s how we ended up with Beyonce, which now means ‘Beyond Others.’ Over 1000 Beyoncés alone were born between 2000 and 2004, when Destiny’s Child peaked and she first went solo, and having that name is a lot to live up to. I imagine its like when people name their kids Jesus.

Yes, Name Discrimination Is Real

Levitt and Fryer’s research in 2004 found that creative names didn’t have a significant impact on someone’s life— using the data of 16 million births in California between 1961 and 2000. They also found that unique names were more common among the lower class, but not that these names contributed to them being lower class. Argued Fryer, "It's not really that you're named Kayesha that matters, it's that you live in a community where you're likely to get that name that matters.” At the same time, a conflicting study in Chicago entitled “Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal?” responded “to 1,300 classified ads with dummy resumes, the authors found Black-sounding names were 50 percent less likely to get a callback than white-sounding names with comparable resumes.” It added, “Applicants with white names need to send about 10 resumes to get one callback, whereas applicants with African-American names need to send about 15 resumes to achieve the same result.” The sample size, method, and location no doubt impacted the different findings, but as time has gone by, the idea that Black names are discriminated against has increased. In the wake of the Great Recession, the New York Times reported in 2009 that people were trying to “whiten their resume” to find employment by dropping or altering names that were distinctly Black.

In a 2015 study at UCLA featuring 1500 participants, the names Jamal, DeShawn, and Darnell were pitted against Connor, Wyatt and Garrett to test for bias. Summed up one of the research scientists, “I’ve never been so disgusted by my own data. The amount that our study participants assumed based only on a name was remarkable. A character with a Black-sounding name was assumed to be physically larger, more prone to aggression, and lower in status than a character with a white-sounding name.” The University of Chicago and the University of California Berkeley did a study that was published in 2021. They submitted over 83,000 entry-level job applications to 108 Fortune 500 companies in the US and found that [people with] Black names had a 2.1% less chance of getting contacted.”

But can Black names have a positive impact on one's life?

Interestingly, Trevon Logan, Lisa Cook, and John Parman, studying death records of three million Black men from four states, found that those with distinctly Black names lived nearly one year longer than other Black Americans. They wrote, “The results show that having an African American name (column I) increases the lifespan by more than three years in Alabama (3.48), two years in Illinois (2.48) more than seven years in Missouri (7.52) and nearly four years in North Carolina (3.93),” leaving them to conclude that “there are likely several pieces of the African American demographic experience which remain hidden from contemporary scholarship and which require serious and sustained investigation.”

Wow!

Comments