8 Black Food History Facts

- Elexus Jionde

- Jun 5, 2025

- 16 min read

Love food history? Love black history? Combine the two with these eight facts!

Amos’s Cookies

Wallace “Wally” Amos was born in Tallahassee in 1936. After moving to New York City in 1948, he’d bake cookies with his favorite aunt, Della. Years later, after dropping out of high school when working as a talent agent, he was the first black one at William Morris Agency and signed Simon and Garfunkel while heading the rock department. When wrong potential clients, he’d give them a bag of his freshly-baked cookies— eventually leading to Marvin Gaye and Helen Reddy investing $25,000 in a cookie store on Sunset blvd. Famous Amos led the gourmet cookie charge, selling $300,000 worth of cookies in his first year, more than 1 million in the next, and 12 million by 1982. Early press coverage emphasized the exclusivity of Famous Amos cookies, and their expensive price— $3.50 for a one pound bag in 1978. To put that in perspective, that’s $16.94 today, when Famous Amos cookies are available pretty much everywhere. But in the 70s and 80s, they were novel. Diana Ross and Jack Nicholson were reported fans. Companies could also buy them wholesale, but it wasn’t convenience stores in the early days. In 1976, it was reported that Bloomingdales ordered 5,000 bags a week.

“Since the first Famous Amos store opened on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood on March 10, 1975, the gourmet cookie business has grown fatter and fatter. Precise figures are hard to come by, but Nation’s Restaurant News, a trade journal, estimates that high-priced cookies generate $500 million a year in over-the-counter sales and at least that much through supermarkets.” Reported the LA Times in 1985 when Famous Amos had 70 outlets, 68 of them franchises cranking out pecan, peanut butter, and butter scotch.

But this profitability would not last.The problem? Amos was bad at business and never hired the proper manager. He sold his majority stake in 1988, losing access to the Famous Amos name brand he created. He’d go on to create Uncle Noname’s low fat and fat free muffins in 1992, which struggled until 1999 when Keebler allowed him to use “Uncle Wally”. He also agreed to promote Famous Amos again for an undisclosed fee, after making Keebler change the recipe. He said, ’’Somehow or another caramel coloring had been added and I don't know why that was. And they were using a real low-grade vanilla flavoring, and I always used vanilla extract. One of the first things I shared with Keebler when we met was that I couldn't promote the product they were currently selling… we had to make some adjustments so that it could be closer to a Wally Amos product.’' Throughout his business endeavors, Amos was also a pro-literacy advocate and prolific author.

Drinks and Cocktails

Like with food, the creation of beer, wine, and liquor could lead not just to financial freedom, but actual freedom. In 1808, 16-year-old Patsy Young escaped enslavement and kept herself afloat in North Carolina by brewing beer. In the 1850s, Tennessee preacher, grocer, and distiller Dan Call enslaved a man named Nathan Nearest Green, whose son is likely pictured here. When slavery was over, he continued to work at Call’s distillery, where, according to oral history, he taught an eight-year-old Jack Daniel how to make whiskey. Call introduced ‘Uncle Nearest as "the best whiskey maker that I know of.” This part of the story, while passed down in oral tradition around Lynchburg Tennessee, was omitted from the company’s official narrative until 2016. Whiskey itself would be advertised by numerous companies with racist imagery, and developed a negative connotation n the black community. As for Nathan, his descendant Yvette J Green recounted in an essay for salon that he was born in 1843 and had a personal estate worth $450 by 1870-- approximately $10,837. He had at least nine children with his wife, Harriet Lou, and earned a living as a farmer.

In the 30s, Zora Neale Hurston tasted “Coon Dick” or bootleg moonshine in Florida, noted to be made of “grape fruit juice, corn meal mash, beef bones, and a few mo things.” It wasn’t pleasant, and she’d write, “The raw likker… was too much. The minute it touched my lips, the top of my head flew off. I spat it out and ate some peanuts.” In the 1950s, cognac brand Hennessy became one of the first to advertise directly to black Americans in the pages of Ebony and Jet Magazines, and they became the first corporate sponsor of the NAACP. Why? They noticed that black veterans who had served in Europe preferred cognac over whiskey, which, again, had a racist connotation. A cultural affinity was cultivated, and yak, namely Hennessy, was locked in. You can learn A BUNCH about black people and beverages in Toni Tipton Martin’s amazing book, Juke Joints, Jazz Clubs, and Juice.

Edna Lewis

Edna Lewis was born in 1916 in Freetown Virginia, the granddaughter of one of the town's founders, Chester Lewis. With most of her family being farmers, she decided early that “a vegetable grown in an open field never tastes as good as one grown in a small garden.” Fast forward to the 1940s. While living in New York as a seamstress or prop-stylist, depending on the source, (who once made or styled a dress for Marilyn Monroe) and communist organizer, she threw dinner parties for friends that led to a job as a head chef at Cafe Nicholson in 1949, a bohemian and creative hangout. Over Lewis’s roasted chicken with herbs and chocolate souflee described as “light as a dandelion seed in the wind,” diners like Truman Capote, Rita Hayworth, and William Faulkner, would pontificate and socialize. After five years, Ms. Lewis moved on to pheasant farming and catering, and later issued two cookbooks, the most popular being 1975’s Taste of Country Cooking. It featured recipes evocative of Ms. Lewis’s childhood, like beef a la mode, first cabbage of the season with scallions, hot buttered beats, pearl muffins and biscuits, and spiced pears. She preferred pan fried chicken to deep fried.

At the time she was working as a teaching assistant at the African Hall in the American Museum of Natural History. The cookbook renewed her cooking career and was invited to cook at trendy restaurants. She proudly recalled serving roast pork to James Beard and Julia Child at Huberts, a French bistro. In fact, in 1976, James Beard raved about her cookbook, and was startled to realize the Edna who wrote the book was the same Edna who served marvelous food at a “small intimate New York restaurant,” many years ago, assumedly at Cafe Nicholson. In the 80s she was the chef at Fearrington House Inn in Pittsboro North Carolina, which Aaron Hutcherson said still has her chocolate souflee on the menu. In 1988 she delighted that quality fresh vegetables were being offered in New York at the Union Square Greenmarket.

Known as the “Julia Child of The South”, Ms Lewis was profiled by the Washington Post in 1990, “What Lewis remembers from growing up in Freetown, Va… is freshly churned butter and home-rendered lard… eel or catfish snatched from a nearby stream; wild greens, berries and nuts, foraged from the fields and woods; fruits plucked from a tree in the front yard and eaten on the walk back to the house. There was always food for friends or travelers who stopped by, maybe a slice of freshly baked pound cake…There were always lively discussions around the dinner table and big meals, prepared in the days when a man wouldn't marry a woman unless she was a good cook.” She added that country and soul food wasn’t “all fried chicken and greens." At the time, she was 74 years old and working six days a week from 7 AM to 9PM at the historic Gage and Tollner in New York, a restaurant that had refused black people service until 1960. She was credited with reviving the restaurant with her dishes, including she-crab soup, crab cakes, and barbecue ribs. She retired in 1992 at 75, the age she promised herself she would do so.

Edna’s influence on the culinary world would resurface in 2017 when most competitors on an episode of Top Chef didn’t know how to make a dish that reflected her. Her 1975 cookbook promptly entered the best sellers list. In November 2022, the Orange County Office of Tourism in Virginia launched The Edna Lewis Menu Trail, showcasing restaurants featuring her recipes like this delicious-looking Apple Brown Betty (pictured below) at Gordonsville Ice House in Gordonsville, Va.

Hip Hop

"Have you ever went over to a friend's house to eat and the food just ain't no good? I mean, the macaroni's soggy, the peas are mushed, and the chicken tastes like wood?”

Rapped Wonder Mike in Rappers Delight. If you’re a conniseuer of black literature, you know that food in storytelling and imagery is quite common— and because hip hop is the extension of the black literary tradition, its no surprise how integral food is to hip hop. Of course, there’s the slang. In “Aquemini,” André 3000 rapped. “Street scholars majoring in culinary arts / You know, how to work bread, cheese and dough.” Food also conveys a lack of funds, whether you’re Bigge Eating sardines for dinner (Biggie) or Every motherfuckin' night, I was eatin' cheese eggs like Megan Thee Stallion. With cash flow comes grey poupon, lobster, caviar, bowls of ziti, and name-dropping expensive restaurants like Mr Chows, Tao, and Nobu. But restaurants also convey hometown pride, from Beyonce namedropping Frenchy's to southerners and Pappadeaux and Waffle House, and any number of West Coast rappers dropping Roscoes Chicken and Waffles and Atlanta-based musicians shouting out the wings at Magic City. I can’t decide which female rapper loves food more, out of Latto and Dojo Cat. And Sweetie loves her creative food combos, which made her prime for endorsement deals, like a bunch of other rappers. Hip Hop is arguably one of McDonald’s biggest marketing tools. There’s a lot of delicious food metaphors for sex, which we discuss in this video. But the food scene extends past lyrics.

In 1994 used $40,000 raised from friends and family to stat Rap Snacks, using the flavors Bar-B-Quin’ With My Honey and Back At The Ranch. One of the first rappers to become involved was Master P. My grandfather used to carry these in his convenience stores and they’d have rappers like Lil Romeo, Bell Biv Devoe, and Warren G.

In 1997, the same year that Cooking Light decreed that Soul Food was the cuisine to watch, Diddy launched Justin’s. The New Yorker described it thusly: (The crowd sometimes mistakes the place for a late-night club, and it shows.) The fried-chicken plate—with a side of mac and cheese—is delicious, and so is P. Diddy’s Jumbo Fried Shrimp, which one waiter referred to as the “Puffy Shrimp…” This was just the beginning of hip hop destination establishments that added to the legitimacy of problematic moguls like Diddy, who also extended their brands to being ambassadors for top-shelf alcohol.

Other rappers have entered the world of franchising, like Rick Ross and Wing Stop, or got into vlogging and cookbooks like Coolio and The Ghetto Gourmet and Snoop Dogg’s From Crook to Cook. A cookbook honestly makes sense for any stoner. Kelis went from Tasty and Milkshake to Food and Farming, eventually graduating from Le Cordon Bleu. Sauce was her specialty, explaining that its “what accessories are to a woman's outfit. Sauce defines where the dish is from and who's making it...I think everything is better smothered, poured, or dipped." She’s also got cookbooks and a bunch of other food-related media. Lastly for the hip hop segment, I’ll leave you with Gucci Man’s Ice Cream Tattoo and the Wutang song Ice Cream.

Jemima, Rastus, and Ben

In 1889, pancake flour entrepreneur Chris Rutt heard blackface vaudeville performers sing a song called Aunt Jemima. He made this the name of his pancake mix. In 1890 the new owner of the formula commissioned 56 year old former enslaved woman Nancy Green as the spokesperson of Aunt Jemima pancakes. Aunt Jemima was a part of a larger nostalgia advertising trend of appealing to white desires to return to the old status quo. The character was crafted with a scarf and apron as symbols of her servitude. At the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago, Jemima delighted patrons as a jovial and friendly storyteller who wanted to keep everybody happy and fed. Aunt Jemima’s kind and cheerful face was slapped on merchandise and advertisements that perpetuated the stereotype of the mammy, who adored taking care of white people during slavery. Ads emphasized Jemima's role in taking care of a white family with her loving pancakes, and ad execs played up the fact that her recipe was passed down from slavery.

Another debut at the 1893 Worlds Fair was Cream of Wheat, which featured the character “Rastus” which was a slur for black men. The dumb Rastus was a recurring archetype in minstrel shows, so the selection for Cream of Wheat was deliberate. The company switched to a supposed picture of a Chicago chef named Frank L White. According to an ad executive,” I noticed particularly two colored waiters who had unusually winning smiles...I then offered each of them fifty cents if they would go down to Copland's Studio, which was only a few doors away, and have their pictures taken. This impressed them as a great joke but they willingly consented. I had about a dozen pictures taken and the one which I liked best showed the negro with one tooth missing, so I arranged to have the photographer re-touch the photo...That marked the birth of the new "Rastus," now so well known to the American public.”

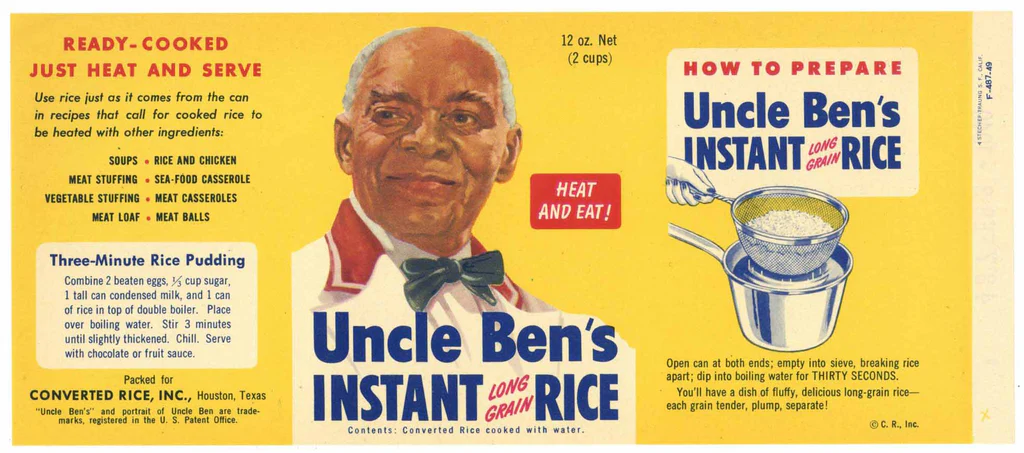

Before Uncle Ben in Spiderman, there was Uncle Ben's Rice by the Mars Food Company, first hitting the shelves with the bow-tie gentlemen in 1946. Execs would claim Uncle Ben was based off of a real rice-grower, as if using somebody’s likeness without payment was better. Symbols of black subservience was in for a lot of brands throughout the 20th century Though Aunt Jemima went through a variety of physical changes over the years, the trademark rag on her head remained in place until 1989.. In 2007, Uncle Bens spent $20 million to rebrand Uncle Ben into an “executive”, with the New York Times describing: “an accomplished businessman with an opulent office, a busy schedule, an extensive travel itinerary and a penchant for sharing what the company calls his “grains of wisdom” about rice and life.” In 2020, in the aftermath of market-wide panic in the wake of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, all three companies rebranded.

Kitchen Testing

When Ebony Magazine began operating out of the new Johnson Publishing Company headquarters in Chicago in 1972, it featured a full spread showing off its new home at 820 South Michigan Avenue. The Test Kitchen was the envy of the building. Which is hard because the entire building was beautiful— just check out John Johnson’s executive suite and bathroom. If I was alive in the 60s it would have been my destiny to work in this building, but lets stay on topic. Recipes had been in the magazine since 1946 as "Date With a Dish”, but now things like Cherry Pompadour Pie were whipped up in this funky and groovy space on the tenth floor— which was also home to the Ebony employee cafeteria. It was the third such kitchen, but this one was all electric, featuring a trash compactor, a four-slot toaster built into the wall, a built-in can opener, an inset microwave, and a refrigerator had an ice and water dispenser.

Ebony’s first food editor was Freda DeKnight, who was the first black food editor in the country. [CLIP] She put directions as captions for the magazine's photos, which was extremely popular. DeKnight published 1948’s’ A Date With a Dish: The Ebony Cookbook. Thousands of recipes from regular people, celebrities, and foodies, multiple versions of different dishes, like fifteen recipes for cornbread. She wrote, "It is a fallacy, long disproved, that Negro cooks, chefs, caterers and homemakers can adapt themselves only to the standard Southern dishes, such as fried chicken, greens, corn pone and hot breads. Like other Americans living in various sections of the country they have naturally shown a desire to become versatile in the preparation of any dish, whether it is Spanish, Italian, French, Balinese or East Indian in origin.” There were regional specialties like Banana Orange Caramel Cake, which Donna Battle Pierce made here, Tamale Pie, a New Orleans Po Boys recipe offered up by two graduates of Xavier Univeristy, Charlie Saunder's Hot Water Cornbread in the “Collectors Corner”— only available in the 1948 edition. It was reissued as The Ebony Cookbook in 1962, with “416 recipe-packed pages.”

Another food editor, Charla Draper launched Your Favorite Recipe column, testing readers recipes and letting employees taste and vote, while working at Ebony from 1982-1984. Per the Landmark Illinois, “Taste testers would fill out an evaluation, eat a soda cracker to cleanse their palate and return to the counter for the next recipe. The winning reader recipe would be featured in the magazine and receive a $25 cash prize. Draper specifically recalls a delicious sweet potato pie recipe that was a personal favorite from this column.” Food Editor Charlotte Lyons, who served as food editor between 1985 and 2010, said “They just always liked to hang out in the test kitchen. If I was cooking, they were tasting.” Ebony never upgraded or changed the design of the kitchen- only replacing the refrigerator once. After Ebony folded and the building was sold, the test kitchen was saved from demolition, dismantled piece by piece in one weekend, and displayed in the the Museum of Food and Drink before being relocated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

/

New York's Soul Food Scene

In 1969, Bergdorf Goodman held a charity fashion show called “Basic Black” for the Harlem Northside Children Center that was catered with soul food— including chitlins and champagne. Said a chairwoman quoted as Mrs. Charles Taylor, “it’s all very in and chic to be eating soul food here at Bergdorf’s…we should remember that this once was the only food poor blacks had. And it didn’t use to be all that good.” The city’s soul food culture was flourishing. In 1962, South Carolina-born Sylvia Woods and her husband, Herbert, founded Sylvia’s in Harlem. The space had formerly been Johnson’s Luncheonette, which Sylvia had worked at as a waitress for a number of years before buying it for $20,000. Originally encompassing eight counter stools and four tables, the earliest menu featured breakfast like biscuits and gravy, but more customers and longer hours meant a bigger menu. Described Osaka Endolyn, “I knew that the food we only ever had at Thanksgiving and Christmas was available all the time — all the time! — and that the same faces I saw in the pages of Essence and Ebony magazines on our coffee table could be spotted there, sometimes together.”

Early fans included James Brown and Roberta Flack, the latter of whom said her favorite meal was “Grilled chicken liver with tons of grilled onions and scrambled eggs, medium. Oh, yeah.” A 1979 article by New York Magazine food critic Gael Green brought a new clientele. Wrote Green despite criticizing the okra and black eyed peas, “It’s an adventure. It’s a lark. The grits are a must. They are impeccable, smooth and full of the nutty hominy flavor.” And the ribs? “Moist and sassy.”

People flocked to the tiny restaurant and Sylvia’s expanded into next door, eventually being in Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever, and becoming known for its Sunday Gospel Brunch Open Mic Nights, live jazz, and line of soul food products. There were even brief entries into the Atlanta market in the 90s, but its true value was in being a beacon of soul food in New York City. The restaurant re-entered headlines in 2007 when Bill O’Reiley ate there with Al Sharpton and claimed to be shocked that black people and businesses were normal. After dining on the meatloaf special, coconut shrimp, and iced tea, he said, “It was like going into an Italian restaurant in an all-white suburb in the sense of people were sitting there, and they were ordering and having fun…And there wasn’t any kind of craziness at all.”

Well duh. Discussions of class and decorum in black restaurants are often tangled in what kind of food is being served. Take another New York one-time hotspot, B. Smiths. The former model B Smith was a hostess at a restaurant named America in the 80s when she impressed the restaurant group owners so much they decided to give her her own eatery, which she paired with cookbooks, entertaining guides, and a tv show, earning the annoying nickname “The Black Martha Stewart. ‘

Said Otis Graham, “She has given the black upper classes permission to come out of the closet,. Everybody in our crowd really watches her show because we live like this. Until now, we felt as though we had to apologize for the fact that we had nice homes and nice things.” While Sylvia’s was seen as southern and traditional, B Smith’s restaurants and brand was seen as innovative and classy soul food for middle-class black professionals. Described Jessica B Harris, “The menu revived old southern favorites like fried green tomatoes, crab cakes, macaroni and cheese, and mashed sweet potatoes, and it also gave a nod to Caribbean influences with pigeon peas and rice and fried plantains. They were served alongside dishes like curried coconut oysters with a coconut wasabi dip and “Swamp Thang”, a haute of shrimps, scallops, and crayfish napped with a Dijon mustard sauce and presented over a bed of greens.”

A New York Times article encouraged the restaurant’s elitist PR, writing about a slew of couples who met their mates over B. Smith's meals. “All three couples are black, and the place where they met, B. Smith's Restaurant at 47th Street and Eighth Avenue, has emerged as one of New York City's principal meeting places for black professionals. Since it opened on Nov. 22, 1986, four black couples who met there have married, including its owner…” B. Smith would open two more restaurants in Sag Harbor and Washington DC.

Described one paper, “While Smith may have grown up eating collard greens from her own back yard, she now sautes them in olive oil and puts them in Italian frittatas.” This reflected a shift in soul food in the nineties, especially in New York. Reported the Times in 1995, “Something has happened to soul food of late. The dishes are often fancier, and sometimes healthier than the meals prepared by grandmas in sweltering Southern kitchens or by cooks uptown at Sylvia’s… Call it nouvelle soul.” The new wave of southern cooking was converging with efforts to honor pioneers like Edna Lewis. At Alexander Smalls’ Cafe Beulah, described the paper, “well-heeled neighborhood residents and luminaries like Naomi Campbell, Quincy Jones, Glenn Close, Bernadette Peters and Toni Morrison (she has actually invested in the restaurant), sup on black-eyed pea and arugula salad with honey mustard dressing and sauteed chicken livers with peppered turnip greens and barbecue mustard sauce.” The paper added, “In traditional Southern cooking, collard greens are cooked for at least an hour, sometimes for two or three. But not at Cafe Beulah, where Mr. Smalls sautees them in olive oil, garlic and rosemary for a scant 10 minutes.”

Another noveau restaurant opened by a former model, Toukie’s, was health focused. Toukie Smith, ex-partner of Robert DeNiro, had gained weight in 1987 after the loss of her brother, the designer Willi Smith, to HIV/AIDS. Wrote the Times, I “IMAGINE barbecued ribs without sugar or salt. Or candied sweet potatoes with the barest sprinkle of brown sugar. Biscuits without much butter.” Added Hilton Als for the New Yorker, “Toukie’s menu is one of the most autobiographical we have ever seen—offerings include “My My Those Fries,” “Honey That House Salad,” and “Black Bottom Pie.” Beulahs and Toukies would be bested by places like Miss Mamie’s Spoonbread Too, a continuation of former model Norma Jean Darden’s Spoonbread Catering, which got its start supplying the actors and crew of The Cosby Show.

Praline Ladies

Read an 1895 copy of Current Literature, “Ask the ebony woman how to make this delicious brown sugar and pecan candy, and she will nod her head mysteriously and give you an indefinite answer, for the secret is her own, and she does not intend to reveal it.” The mystique of pralines began from a recipe brought from France into New Orleans. While the original French version was a combination of almonds and sugar, in the crescent city, the almonds were swapped with pecans and splashed with cream. Because of the abundance of free pecans growing around New Orleans, praline were a low cost business for the mostly black female street vendors who sold them. By 1918, a white owned New Orlean company capitalized on "this old Louisiana mammy confection,” and pralines became common sweet shop treats featuring mammy stereotyping. In 1984, Loretta Harrison created the first black owned praline company in New Orleans, Loretta’s Authentic Pralines, after being a smash hit at Jazz Fest the previous year. She sold $1500 pralines for $1 apiece because the regular praline vendor dropped out— which is approximately $4700 in today's money. In her shop, she innovated with new flavors like chocolate, rum raisin, and peanut butter.

Comments