Can Black People Swim?

- Elexus Jionde

- Apr 20, 2025

- 5 min read

There are many reasons to learn how to swim. Its a useful zombie apocalypse skill, its great exercise and easy on the joints, its a stress reliever, its fun, and you never know when you’ll need to help your fellow black people in a fight against racists. Plus, its a really cool way to reclaim our history. See how many facts you know about the history of Black people and swimming below.

Most pre-colonial West Africans knew how to swim for hunting, fishing, and traveling purposes.

People lived near lakes, rivers, and the ocean— so swimming was akin to survival, but also a spiritual and mystical experience. Plus if you wanted to bathe— you needed to know how to move in water. While West african toddlers began learning to swim between 10-14 months or 2-3 years old, most Europeans didn’t know how to swim. According to Kevin Dawson, author of Undercurrents of Power Europeans were amazed at African swimming abilities— particularly their freestyle techniques opposed to the breaststroke— comparing them to the dangerous and lusty mermaids and labeling them as amphibious.

The name 'Underground Railroad' was born thanks to an enslaved man who swam away from his enslavers.

In 1831, an enslaved man named Tice Davids fled from his Kentucky enslaver by jumping into the Ohio river to swim across to the free state of Ohio. He was never found, but his disgruntled owner said he “must have gone off on an underground road.” While its unknown if Davids made it to freedom, this is how the name the ‘Underground Railroad’ was born.

Many slaves were not allowed to swim or learn how to swim.

Early accounts of slave traders showed that they learned quickly to keep their victims restrained when near bodies of water, because it wasn’t uncommon for Africans to flee bondage by trying to swim away— or intentionally drowning themselves. Swimming provided a means of transportation for the enslaved, which slavers could not have.

Swimming began being taught in the states as a Public Education effort but Black people were not a priority.

After the civil war, more complete death records, the increasing use of autopsies, and a larger population meant a rise in drowning deaths were reported. Scores of white people were taught to swim in public education efforts. The first municipal pool, separated by gender, was opened in Boston in 1868. Others would follow in various cities, built in white neighborhoods while avoiding black ones. In 1914, in Pasadena California, non-white people were restricted to pool use on the morning that it was cleaned. When black people protested, the city officially made the pool whites only, saying if it was integrated people wouldn’t use it. When the pool was integrated in 1947, it was shut down the following year as white people flocked to their own private clubs and neighborhoods.

White fragility and insecurity played a part in the lack of pool integration.

Jeff Wiltse, author of Contested Waters A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, detailed how the 1920s and 30s saw thousands of new outdoor public pools, many of them extremely fancy. By this period, they were no longer gender segregated—but in the wake of the great migration, they were whites only— like when the federal government segregated pools in DCin 1926. White men were terrified of black men being around white women in bathing suits. Wrote Wiltse, “the concern was the black Americans, black men, would take advantage of the pool environment, to brush up against white women, to touch them in the water, to visually consume them, as they were wearing, you know, relatively-tight-fitting, relatively-revealing swimsuits. And this sort of played into a psychology of needing to separate black men from white women.”

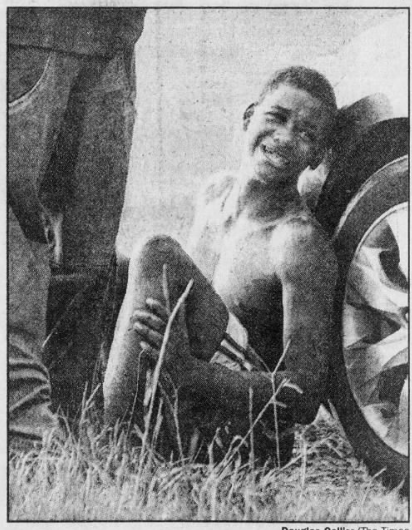

Public beaches were also subject to the same segregation as Public Pools.

In Chicago in 1919, a 17-year old black boy named Eugene Williams was at the black area of the beach when the raft he and his friends were on floated into the white area. A racist began throwing rocks at Eugene, who couldn’t swim. He was struck by one, fell into the water, and drowned. This triggered a riot that ended with 23 black people dead and a wave of arsons that left 1-2000 people homeless. While that Chicago beach was public, the coastal land owned by black people across the country— like Bruce’s Beach in Los Angeles, would only be snapped up via imminent domain, or subject to violence and arson in the decades to come. So a lack of private beach access compounded racist public beaches and pools.

Private pool clubs came into existence because of racism.

Plenty of pools desegregated before the 1964 Civil Rights Act, but many public pools were unwelcoming or downright hostile— and when forced to integrate, many pools simply closed while white people went to pool clubs, and increasingly built private pools in their backyards. Remarked the Florida Attorney General in 1955, “the idea of children of mixed races in swimming pools is against the public attitude.” After the Civil Rights Act, a bunch of public pools closed and private pool clubs— similar to country clubs or segregation academies— opened. In 1967, Mr Rogers hosted Francois Clemmons, on his popular children’s show, featuring them dunking their feet together in a kiddie pool— something they’d do again in the 90s. In 1973, the supreme court ruled that private swim clubs couldn’t discriminate because of race. Public pools would reopen over the next decade, but never at previous rates— plus many of them ended up closed because of the devolution of public services. People built private pools in their backyards.

64% of black American children can’t swim compared to 40% of white kids.

The USA Swimming Foundation found that a child is only 13% likely to learn how to swim if their parents don’t know how. In August 2010 in Shreveport Louisiana, Dekendrix Warner wandered away from his group of roughly 20 friends and relatives enjoying a picnic in a recreational area of Shreveport. The area was not open to the public— and for good reason— when Dekendrix waded into the water of the Red River, he stepped into a deep trench and was swept away by the tide. Six black teenagers, all related to Dekendrix, and between the ages of thirteen and eighteen, died trying to save their cousin. Remarked a witness, ”None of us could swim. They were yelling 'help me, help me. Somebody please help me.' It was nothing I could do but watch them drown one by one.” One woman named Maude lost three of her children in the tragedy, saying “its hard when you see your kids drowning and you can’t save them.”

In 1981 Charles Charlie “The Tuna” Chapman was the first black man and the 220th person ever to cross the English Channel, a 21 mile journey.

A drug trafficking charge in the early 90s led to prison time, but in 1997 he swam around Alcatraz Island twice, in his continued efforts to de-stigmatize swimming for black youth.

In order to combat the statistics within the Black Community when it comes to swimming, many modern day organizations have popped up.

In the US, approximately 3500-4000 people drown accidentally per year— and its the leading cause of death for children ages 1-4. Additionally, there are 8000 non-fatal drownings a year. The majority of adults worldwide can’t swim, and ability is impacted by location and access. As recently as 2021, it was reported that 64% of black American children can’t swim compared to 40% of white kids— up from 58% in 2008.Modern organizations have been combatting this ugly reality, like Black Girls Dive, We Can Swim Philly, Make a Splash, Swim Up DC, and Black Kids Swim. In 2019 at the Nile Swim Club in Yeadon, according to the New York Times, they started “No Child Will Drown in Our Town,” offering 10 days of free swimming lessons to anyone who signs up.” There are programs for adults too.

Did you enjoy this lesson on Black Swimming History? Check out the full video on Youtube!

Click Here To Get Further Sources and Reading

Comments