How Black People Partied In the Past

- Elexus Jionde

- Apr 25, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: May 22, 2025

No matter the era, black people have always made time for a party. Here's a quick list of black party facts from Juneteenth, Black Bike Week, Harlem Rent Parties, Juke Joints, Freaknik, and even the days of enslavement.

Partying Despite Enslavement

Even during slavery, some black people found time to party. Wrote historian Stephanie M.H. Camp, “deep in the woods, away from slaveholding eyes, they held secret parties, where they amused themselves dancing, performing music, drinking alcohol, and courting.” These party-goers were sometimes judged by their more religious peers.

What Inspired The Sugar Shack by Ernie Barnes?

Ernie Barnes, the NFL player and painter of 1971’s The Sugar Shack, was inspired by a childhood incident in Durham, North Carolina when he snuck into a black dance hall and witnessed the jubilant crowd dancing and enjoying themselves. He’d recall, it was the “first time my innocence met with the sins of dance.”

Juke Joints

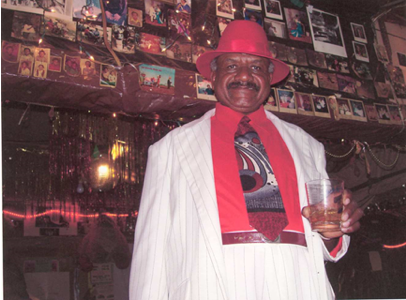

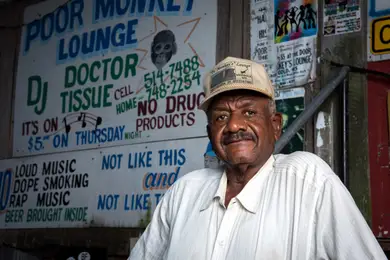

Parties in discreet rural venues, called “juke joints,” would sometimes pay off local law enforcement or to avoid charges for selling liquor in dry states and counties. Historians debate the origin of the word “jook,” tying the word to either the jooba dance of enslaved Congolese living in Charleston, South Carolina — or the Gullah-Geechee word for infamous or disorderly, “juk.” Many of the famous jukes in states like Mississippi that flourished in the 20th century closed by the 90s and 2000s because of new nightlife options and legal riverboat gambling. Willie Seaberry would treat nights at his Poor Monkey’s juke as a fashion show, emerging in a new brightly color-coordinated suit every hour of the night. He opened his Merrigold, Mississippi establishment in the 50s and operated it until 2016, when he died at 75.

Juneteenth Spreads

When one black Texan was asked to recall his first Juneteenth in Los Angeles, he said, “Come June 19th of 1949 I asked, ‘Why is everybody going to work? Why are the banks open. I couldn’t believe it.” He started grilling and taking the day off. He was one of thousands of transplants spreading the celebration outside of Texas. Though Juneteenth celebrations slowed down in the Jim Crow era, they were happening again on a wider scale in the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s and beyond. Texas, birthplace of the original 1865 celebrations, was the first state to make it an official holiday in 1980. Here’s a video from the first official Austin, Texas parade:

Black Bike Week

The first Black Bike Week in Atlantic Beach, South Carolina in 1980 drew about 100 black attendees who felt excluded from the white bike rallies where Harley-Davidsons dominated. Atlantic Beach for decades was the only location for black people, but black bike week eventually spilled into Myrtle Beach in the 90s. “There are nearly twice as many police officers, 550 compared to 300, deployed during Black Bike Week compared with Harley-Davidson Week, held the week before, which drew more than 200,000 mostly white bikers," reported the New York Times in 1993. Complained an angry white observer ten years later, ''Every year, they just take over. They leave so much trash. They ride around sticking their butts out. It's disgusting.'’ Learn more about black bike week in this article.

Harlem Rent Parties

When predatory and racist landlords doubled black tenants’ rent in the 1920s, people in Harlem began to throw “rent parties” with hosts earning 25 to 50 cents per head, to offset rent fees. There was music, booze, food, and, especially for new arrivals, the allure of making connections in a fresh city. In the 1920s, lewd dancing was prominent in the black social scene, close hugging, touching and grinding, being the norm. Contrarily, white critics scandalized the “slow drag” when it appeared in a 1929 Broadway production.

A typical rent party menu included fried chicken, fried fish, corn, pigs feet, pork chops, and potato salad— but because of black immigrant contributions, there were dishes like jerk chicken and ackee and saltfish, too. According to Malcolm X during his early time in Harlem, the streets were littered with “People offering you little cards advertising rent-raising parties…. I went to one of these-thirty or forty Negroes sweating, eating, drinking, dancing, and gambling in a jammed, beat-up apartment, the record player going full blast, the fried chicken or chitlins with potato salad and collard greens for a dollar a plate, and cans of beer or shots of liquor for fifty cents.”

Queer buffet flats and rent parties gave the LGBTQ+ community a safe space to exist and party free of the judgement and gaze of whites found at more tourist-heavy events, like the Hamilton Lodge Ball.

All About Freaknik

Freaknik began in Atlanta in March 1983 as a relatively small picnic featuring “sandwiches, coolers, and boomboxes” for HBCU students in the Atlanta University Center during spring break. When a bunch of members from the DC Metro club were bored and stuck on campus, they threw the first picnic in Piedmont Park. The name for Freaknik was inspired by two songs: Freak by Chic and Freak of The Week by Funkadelic, with a student named Rico Brown saying “lets call it Freaknik.” The money made from the first Freaknik went to local charities. Due to a lack of social media and publicity, the early days saw mostly college attendees who had heard about the event from word of mouth. They gathered in various parks and brought their grills, blankets, boomboxes, and food with them. How did the event grow? Check out the following video to find out!

Learn more about black parties in this video: