10 History Facts About Black Women's Hair

- Elexus Jionde

- May 5, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: May 22, 2025

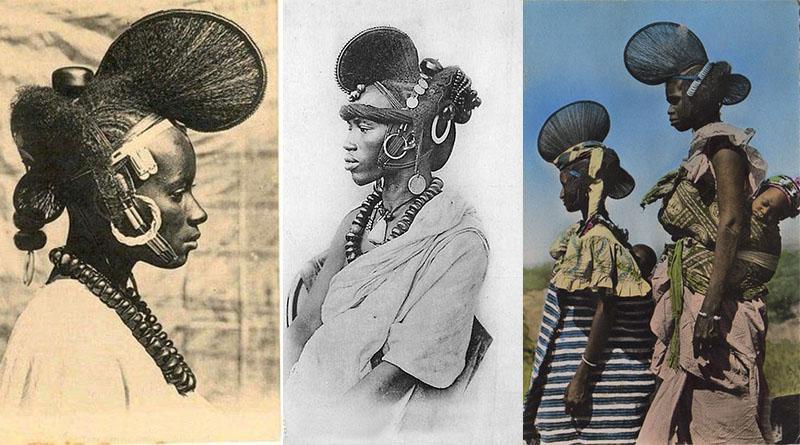

Throughout History the way in which Black Women have worn their hair has constantly shifted with the times. Influenced by our environments, culture and socio political climate. Here's 10 Facts About Black Womens Hair History. Lets see how many you know.

Black hair has been used throughout time as a method of communication.

Among the Wolof, Mende, Mandinka, Fulani, Yoruba, and others, hair could

communicate marital status, religion, ethnic identity, age, wealth, and rank. Some clans even had their own specific hairstyle, so that one could look and see immediately what family they hailed from. Among Wolof people, girls who were not of marrying age partially shaved their heads, and recently widowed women stopped doing their hair for a while to “de-beautify” themselves in a society where hair was central to identity

and beauty. How central? Having unkempt or messy hair could translate to being sad, having loose or no morals, or being dirty. The natural hair that we think of today: unbound, long, unruly, free— was not the norm in most cultures. Basically, if your hair was not done, its meant something was wrong. Additionally, the importance of hair was demonstrated by the fact that it was sometimes used for rituals and spells or as

talismans for protection. Because hair was so important, the hairdresser was revered in these societies, especially because the grueling work took hours or even days. Clearly, hair was practically, socially, spiritually, and aesthetically significant to our ancestors— just like in many cultures around the world. So it’s especially devastating to know that to mark their status as anonymous non-human merchandise, or chattel, most of the

20 million men, women, and children sold into slavery were shaved bald.

Scarves were originally donned by Black Women to make them less attractive to the White Male Gaze.

Colonial Louisiana enacted the Tignon law in 1786, which required black women to wear headscarves to make them less attractive to white men. The scarf was to be worn by the free and the enslaved black women, to dehumanize all. Free black women often decorated theirs, or used expensive fabric, and the tignon briefly became a trend among white women, allegedly beginning with Napoleon Bonaparte’s wife Josephine. The Tignon law was no longer in effect after the US took control of Louisiana in 1803, but it’s no surprise that in the centuries after, headscarves and bonnets on black women have continued to be considered low class.

The idea of having 'Good Hair' can be traced back to slavery.

Enslaved people who worked in the big house or in other positions that put them in close proximity to whites were usually light-skinned, had less kinky hair and higher expectations to keep it neat. Without access to proper hair care, many enslaved resorted to using toxic

substances like kerosene, butter, and animal fat, like hog lard, on their fragile strands. Because they didn’t have combs like the ones used in Africa, they used a sheep fleece carding tool. For many, hair maintenance meant frequent braids, scarves, and dry misshapen Afros. Damaged kinky and curly hair was regularly denounced, especially when in comparison to the tresses of the people born from rape and exploitation from white enslavers. Colorism was compounded by this comparison of good vs bad hair. Black women who were mixed with white or native blood often had wavier and/or longer hair, which was noted by several interviewees in the enslaved narratives. The concept of “good hair”, which was straight or wavy, long and unkinky, versus “bad hair”— kinky, curly, and/or short— materialized.

Hair was considered sacred.

Hair was sacred not just in a way that spoke to ones humanity, but it also was used by hoodoo conjurers and practitioners on plantations. One man mentioned in Texas that conjurers would mix “hair and brass nails and thimbles and needles.” It has also been said, though it’s not verifiable, that some enslaved people who ran away used braids for maps or to transport food. Meanwhile, among free black populations in Boston and Philadelphia, black people who did their hair in similar fashions to white people— whether to imitate for respectability or because they thought it looked good— were mocked and criticized as uppity or pretentious in the emerging minstrel circuit. There were early hairdressers who were free black and made good money servicing white clientele. Think Voodoo priestess Marie Laveau in New Orleans, who collected tea from her clients and used it for the basis of her conjure work and blackmailing.

Items such as Eel Skin would be used to curl hair.

In Texas, a man named Oliver recalled his mother and other women fishing for eel, stripping the skin off, and wrapping it around their hair to “make it curly”. Some women mixed lye

and potato for straightened hair with disastrous results.

The first relaxer was created by Garrett A. Morgan --the man who created the precursor to the Gas Mask.

Sometime between 1905 and 1909, Garrett A Morgan, the future inventor of the precursor to the gas mask, noticed the chemical he was using inadvertently straightened curly wooden fibers. Morgan would go on to manufacture and distribute relaxers and other haircare products like hair coloring and a hot comb, through the GA Morgan Hair Refining Company. Hot combs had been invented in France in the 19th century, but didn’t catch on in America until the 20th century. Garrett had originally sold the relaxer to men before finding a

strong consumer base in black women.

Many Black women were historically forced to straighten their hair in order to find employment.

As Black Americans migrated north during the Great Migration, and black urban hairdressers rose in number, beauty politics about straightened hair and lightened skin became more debated. “Don't remove the kinks from your HAIR. Remove them from your BRAIN,” wrote Marcus Garvey. But black women needed money. And when seeking jobs in urban centers, or when looking for employment in the rural domestic market, some often had no choice but to conform to racist and intra-communal expectations to straighten their hair. But from another perspective— if we consider the amount of hair manipulation among black women in pre-colonial Africa, the desire to adapt a style, even if it was wrapped up in politics, isn’t shocking. Nor is it shocking that once hair was straightened, black women put their own spins

on styles— not outright copying the white mainstream. Despite the objection to black women straightening their hair, the average black woman trying to survive and/or feel good about herself was wrapped up not just in racist pressure, but in a desire for community or being

on trend, and broader expectations about what we each as individuals owed to the black community especially as racism ramped up in violent massacres and lynchings through the nadir into Jim Crow.

The patent for the process of getting Extensions was patented in 1951 under the name Hair-Weeve by a science professional named Christina Jenkins.

In 1949, Christina Jenkins, a 29 year old with a science degree from Leland College began developing the nylon scalp base and the technique that would lead to the sew in. At the time, women often kept weave in place with bulky bobby pins and clips. The Shaker Heights Cleveland resident filed a patent in 1951 for the Hair-Weeve, which formally served the purpose of “Permanently attaching commercial hair to live hair.” Jet Magazine mentioned in 1952 that Jenkins caused a trend of women wearing “rainbow colored hair attachments” in Cleveland, where she would eventually run Christina’s HairWeeve Penthouse Salon until 1993.

The rising popularity of Afro wasn't due to trends but was a form of protest.

Every year from 1962 to 1972 on August 17th, Marcus Garvey Day, the Grandassa “Naturally” show featured black women, all with natural hair, and even more importantly, dark skin. “There was lots of controversy because we were protesting how, in Ebony magazine, you couldn’t find an ebony girl,” said Kwame Braithwaite, the creator, a 1st generation Barbados-American photojournalist and activist who formalize Black is Beautiful and destroy the term negro. Jazz singer Abby Lincoln, another notable artist who rocked an afro early, was a collaborator on the Naturally shows along with other members of the African Jazz-Art Society and Studios. The Black is Beautiful campaign was needed. Scores of black children like a young Assata Shakur were used to calling each other black as an insult, hurling the term nappy, and seeing afros as ugly and unkempt. She wrote, “We had never been exposed to any other point of view or any other standard of beauty.” The sentiments of Marcus Garvey, Nannie Helen Burroughs, and others were revived and reverberated in the decade of black power. Initially, to many, wearing a ’Natural’ meant making a conscious choice to make a

political statement.

Relaxers and chemical straighteners have been linked to a higher risk of Uterine cancer.

It was reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute that black women who use chemical hair straighteners and relaxers may have a higher risk of uterine cancer. In a study of black and white women, black women are three times more likely to develop uterine fibroids than white ones. Black women are roughly 60% of the hair relaxer market, which thankfully, is dwindling. Sales dropped from $71 million in 2011 to $30 million in 2021.

Comments