How Style Changed In The '90s

- Elexus Jionde

- Aug 15, 2025

- 12 min read

From 'It Bags' to trendy tattoos to hot new haircuts and fashionista rappers, how did American style change in the nineties?

The Rise of 'It Bags'

The Fendi Baguette was a hot ticket item.

Bags became distinguishable “it” items this decade, which was relatively new. Take the Fendi Baguette bag, which debuted in 1997 and became popularized by Carrie Bradshaw in Sex and the City, alongside another B, Blahnik shoes. The Baguette, which stood out from the big totes of the era, was a hit. Fendi maximized the trend by expanding the bag into hundreds of colorways. “Since the fall of 1997, when the Baguette was introduced, there have been 500 variations, ranging from a $475 black nylon bag to a $12,000 hand-loomed version of which only a handful were made,” wrote Elizabeth Hayt in 1999.

Fendi’s popularity surged so rapidly that a majority stake in the company was acquired by Prada and Louis Vuitton in 1999 for approximately $900 million. Hayt reported on the phenomenon of bag collectors, saying, “The basic black leather bag, a staple of most every woman's wardrobe, looks tired by comparison to newer purses in unusual fabrics or embellished with embroidery, beading, and fur. The accessories market, whether low- or high-end, is peaking in part because of widespread handbag fever.” Hayt also discussed a rise in handbag sales at luxury stores like Barneys, for trendy picks like the Dior Saddle Bag, the Prada Bowling Bag, or Kate Spade bags. This was partly because bags cost a fraction of a designer outfit and could still signal luxury, plus, you could wear them more often. Maybe you couldn’t afford a $3,000 Gucci outfit, but you could possibly afford a $900 Gucci Jackie bag.

Globalization Fed Shoe Crazes and Fast Fashion

Beginning in 1990, Air Jordans were frequently featured in The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. On January 26th, 1992, the same day that Bill and Hillary Clinton would face accusations of marital problems and cheating, it was the Super Bowl. A Bugs Bunny and Michael Jordan advertisement featuring the shoe of the decade would lead to a pitch that created Space Jam, and shoes were a big part of the movie. Sneaker collecting rose during this decade as an abundance of color ways and limited edition drops reached the market— including in Japan, where there were a series of muggings in 1996 and shoe prices rocketed to $600 to 2,000 USD. That $2000 price in particular was for the '95 Air Max Yellow. Said one young man, "I see a lot of people who look like they want my shoes. I get nervous if too many people surround me."

In 1997, the same year that thousands of Vietnamese and Indonesian laborers went on strike at Air Jordan factories for an extra 1 cent an hour, Jordan Brand was established. The workers earned 8 cents a day to Michael Jordan’s 56,000 a day— and this was a hallmark of globalization, the World Trade Organization, and trade at the so-called “end of history.” In Cambodia, because the country was not a member of the WTO, there were no quota limits on exports— sparking a chain of foreign investment and child labor, including by Nike. But in May 1998, amidst reports that 9.1 billion in sales were being drowned out by fallen stock prices, layoffs, and criticism, the company announced reforms that didn’t impress striking factory workers.

Numbers were driving fashion more than ever before. In 1995, executives in the nation’s top apparel companies were enlisted to divulge the challenges and trends facing the industry heading into the next century. Described Paul Smith, “They saw the need, in essence, to speed up the industry’s process of product design, manufacture, and distribution in order to satisfy the ever changing and accelerating demands of retail outlets and their customers.” This cleared the way for fast fashion to thrive in the future, especially when the transition of the world’s garment and manufacturing industries from the Global North to the Global South was complete. Added Smith, “Simultaneously, the place of consumption - and, of course, capital concentration becomes ever more centralized in the North itself, opening up new channels of product distribution, marketing, and retailing.”

Three years before the survey of executives, The Los Angeles Times marveled over the new Express business model. The store, originally launched as a cheaper version of The Limited in 1980, had rebranded in the nineties as a more upscale brand, earning $1 billion in sales by 1991. “The formula? Fashion that appeals to women who have outgrown neon but refuse to dress like matrons, knockoffs of European styles, good service and price tags that are usually $50 or less.” Bragged an analyst about the company’s team of buyers: “One of the advantages Express has over its competitors is speed, the ability to spot a trend and get it on the floor within six weeks after they’ve seen it.” There were a number of lawsuits over this fast and imitative fashion, but it was here to stay.

Lil Kim Made Fashion History

Kimberly Denise Jones was the original hip-hop fashion risk-taker. While her peers were known to be more androgynous—think Queen Latifah and Da Brat— Kim embodied sex appeal and confidence. “Everybody wanted to dress her, photograph her, put makeup on her. Annie Leibovitz, Bruce Weber,” said Christina Murray, an executive at Atlantic Records. Many of her outfits were styled by Misa Hylton.

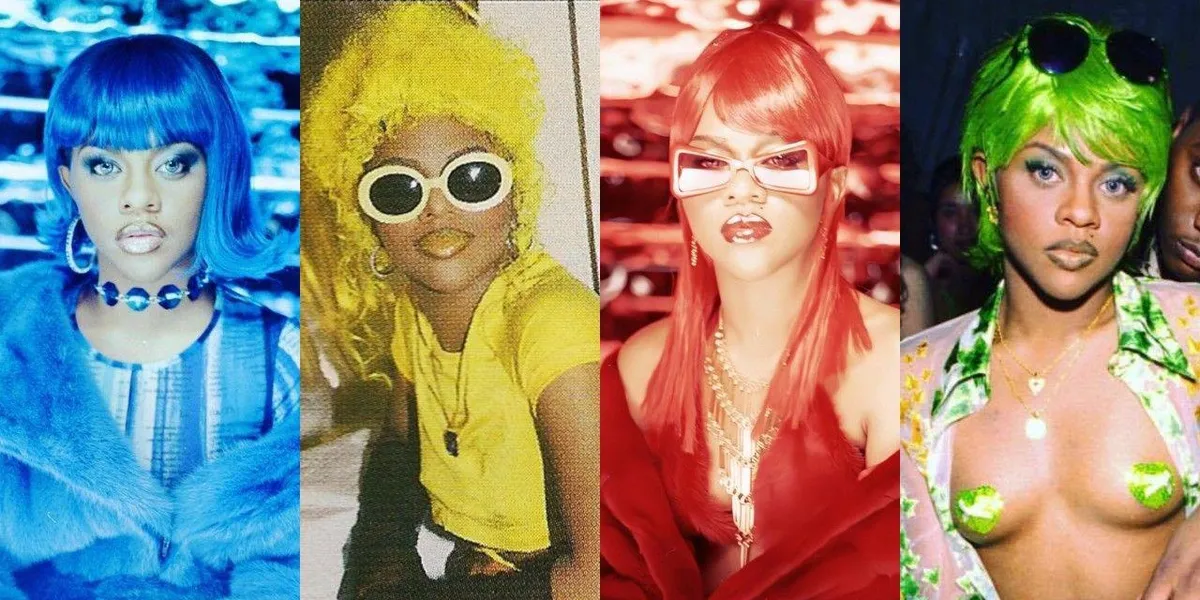

Instead of leaning into quiet luxury and minimalism, Kim was all about logos and maximalism, like the time she wore a catsuit with 965,000 crystals and a bejeweled headcage. Kim referred to herself as “The Black Madonna.” Her lyrics were laced with designer, and she regularly switched up her hairstyles during a time when lace fronts and custom wigs were pricey. For her 1996 debut album Hardcore, the leopard print bikini she wore for the cover was designed by Patricia Field, the soon-to-be Sex and the City costume designer.

Kim signed to Wilhelmina Models in 1998, promoted the brand Candie’s with Brandy, and appeared as Versace’s guest at the 1999 Met Gala, when it was still a super exclusive event. She donned a pink fur coat, a bra, and hot pants that caused a sensation. The matching shoes she wore were too big, but she still made it up the famous stairs of the Metropolitan Museum. Later that year, Kim’s purple look at the Video Music Awards, featuring an exposed breast and matching pasty, was cemented into style history.

Kim’s glamorous and expensive lifestyle was as much a part of her image as the raw sexual bravado and criminal fantasy. Said Jacob York, then-president of her label Undeas Entertainment: “[Kim] wasn’t the wife. She was the high-end side chick to drug dealers. We placed her in a world that we were living in, and it was: You wear all of the finest things because the number one drug dealer, you're his side chick, and he buys you everything. It’s all driven by the male hormones, the male ego, the fantasy. It’s not about love. It’s about being nasty.”

Yikes. While Kim was a fashion girl through and through, and she will always be revered for the risks she took in the nineties, her sartorial choices can’t be viewed without examining her mindset. She said in a 2000 interview, “All my life men have told me I wasn't pretty enough, even the men I was dating. And I'd be like, 'Well, why are you with me, then?' It's always been men putting me down just like my dad. To this day when someone says I'm cute, I can't see it. I don't see it no matter what anybody says.”

By the late nineties, she was rocking blue contacts, which came into fashion just as brightly colored weaves, particularly 613, were gaining popularity. Kim also opened up about her breast implants, just the beginning of her journey with plastic surgery: “That surgery was the most pain I've ever been in in my life. But people made such a big deal about it. White women get them every day. It was to make me look the way I wanted to look. It's my body.” In the same interview, she admitted, “I have low self-esteem and I always have. Guys always cheated on me with women who were European-looking. You know, the long-hair type. Really beautiful women that left me thinking, 'How can I compete with that?' Being a regular Black girl wasn't good enough.”

Before Biggie died in 1997, he was physically and emotionally abusive to Kim in their toxic relationship. It’s hard to say what Kim’s legacy would be if he had not died. Speaking with bell hooks in a 1997 Paper magazine interview, she alluded to Biggie’s emotional abuse, saying, “[He said] you ain't shit without me. You always goin' to need me.” She continued, “Till this day I need that person, so they say, 'You need me. You can't fucking make it without me. You're ugly.'” It’s upsetting that while Kim thrived in the spotlight, this is what the stylish Queen Bee was subjected to behind the scenes, and worse.

Hair Was Political

From the braids on superstar Brandy’s head to the bevy of manes worn by Lil Kim, Janet Jackson, and the ladies of Living Single, and the intricate looks donned by R&B and hip-hop’s favorite women, Black hairstyles of the era were Afrocentric and futuristic. Brandy’s braids, particularly her super-thin micros, reflected an evolution of the hairstyle: it was now common to use extensions, making the concept of them being “natural” a little murky. In 1992, the popular Hype Hair magazine was founded.

Grammy award–winning Lauryn Hill, who rapped about silly girls selling their souls and rocking European weaves (with fake nails done by Koreans), proudly wore dreadlocks on the cover of her album and on the red carpet. Hair, as always, remained political. In the season two episode of Sister, Sister titled Hair Today, Tamera gets her hair straightened and is treated better by the popular clique at school. That same year, Angela Davis wrote about the watering down of the Afro in an article that expressed her discomfort with a March issue of Vibe magazine featuring actress Cynda Williams dressed as her.

Davis was particularly unsettled by Williams recreating her widely publicized FBI wanted poster, writing, “…my legal case is emptied of all content so that it can serve as a commodified backdrop for advertising.” The afro was definitely attached to radical politics in the nineties. Wrote Davis, “A young woman who is a former student of mine has been wearing an Afro during the last few months. Rarely a day passes, she has told me, when she is not greeted with cries of "Angela Davis" from total strangers.” Such hair was often attacked in schools and the work place.

In 1998, a white teacher in Bushwick, Brooklyn, then described by The Washington Post as “a gritty Black and Hispanic neighborhood… notorious for drugs and graffiti”, outraged Black parents when she read the book Nappy Hair to her third-grade students. Written by Carolivia Herron, the book affirmed “nappy hair” and sought to destigmatize kinky tresses. It would go on to sell over 100,000 copies. The white teacher resigned before the outrage died down. The next year, two of 19-year-old tennis player Venus Williams’ signature beads came off her braids during a match at the Australian Open. The umpire penalized Williams a point after the second bead, saying it caused a disturbance, prompting her to yell at him, “There’s no disturbance. No one’s being disturbed!” She was booed by the crowd and, frustrated and unfocused, lost the match. The beaded hair of Serena and Venus Williams had been contentious in the WASP-y world of tennis since they entered the scene in the mid-nineties.

Nearly every Black person had a mom, cousin, or aunt who rocked super short cuts with intricate curls and waves, the kind of style that had to be adoringly maintained monthly, or even bi-weekly. This meant the relationship between hairstylist and client was strong. For Black men in the early nineties, the hi-top fade still carried weight, and more heads were rocking cornrows like Allen Iverson. But no matter the style, for most Black men, crispy edges were usually a must, continuing the important tradition of black barbershops.

For white men, the mullet was out of style by 1993, and the Caesar haircut was popularized by Antonio Banderas and George Clooney. We can’t forget the curtains on teenage heartthrobs like Boy Meets World’s Rider Strong, or the appropriated dreadlocks, either. They also rocked a lot of highlights, gel, and frosted tips. Popular styles for women of all colors included bangs, pixie cuts, super cute butterfly clips, and crimped hair à la Christina Aguilera. And who can forget chunky highlights, claw clips, and Hairagami?

White women weren’t exempt from the politics of hair, either. Big and blonde manes were often associated with bimbos, gold diggers, and ditzes. The perfectly sculpted coif of Texas Governor Ann Richards symbolized the wise and tough Southern grandma. Wrote Texas Monthly in 1992: “Although Republican critics… keep trying to portray her as a shrill feminist liberal, they can’t quite keep her in that ideological box because her hairstyle, washed, curled, teased, and sprayed, is straight out of the fifties, the last era of good feeling in America. Her hair makes her a permanent member of the carhop generation, a throwback to small-town values, which is why she appeals to both men and women.”

When Paula Jones—the Arkansas woman who accused Bill Clinton of sexual harassment—debuted a new look in 1998, it generated widespread news coverage. She looked especially chic at the White House Press Correspondents Dinner in 1998 she was mysteriously invited to. She had elevated her style from what was often mocked as “white trash” by removing her perm and changing her makeup. Said historian Steven Zdatny at the time, “It’s amazing how quickly people recognize social class in hair. There’s a haircut that belongs on Wall Street and a different one that belongs in Hollywood.” The taming of her hair was accompanied by a completely new wardrobe, akin to the makeover in Clueless. Wrote Robin Givhan: “Enough with the dowdy short skirts, cheesy dresses, horrific accessories. A few trips to Nordstrom and Macy’s and a couple of suits later… goodbye, Paula. Hello, Ms. Jones.”

Paula Jones alleged that Bill Clinton propositioned her while he was serving as Governor of Arkansas, something several people attempted to dispute by attacking her looks. The makeover was, sadly, seen as necessary. Wrote The Los Angeles Times, “Any woman suddenly in the glare of TV cameras and news photographers would want to look her best. But in this case, the more attractive Jones looks, the more credible her claim that a public figure would have been willing to risk the kingdom, so to speak, to dally with her. And when she presents herself as an attractive, sophisticated woman instead of a ditzy Southern babe, she has a better chance of being taken seriously.” Makeup artist Cydbe Watson added, “She did it all. She maxed out her capacity for beauty.”

Marcia Clark, the lead prosecutor in the O.J. Simpson murder trial, faced similar criticism during the mid-nineties. She was frequently labeled as unsophisticated and unattractive, largely due to her curly, unstyled hair. Clark was advised to appear more “feminine” and “soft,” and she received a notable boost in favorable news coverage after debuting a shorter and straighter hairstyle. Her hairstylist, Allen Edwards, who charged the prosecutor $150 to break out his scissors, claimed to have received thirty interview requests for the same cut by the end of that news day.

Not all haircuts went over so well, like the 1999 shearing of Keri Russell’s voluminous and curly mane after the first season of The WB’s Felicity. The resulting pixie cut was blamed for a plunge in ratings, despite the fact that the show had been moved to a new time slot. Said an executive for The WB, “We got a lot of emails and letters and feedback from our friends in the industry who were fans of the show. People were disappointed and angry at us and at Keri for cutting off her hair. ‘Who made that decision?’ they asked.” The show’s creators, J.J. Abrams and Matt Reeves, did, but everyone seemed to blame Russell.

Over on NBC, The Rachel, seen on Jennifer Aniston’s character in Friends, was wildly popular for a brief period. It first appeared in the season one episode The One With the Evil Orthodontist. The style was created by Chris McMillan, who convinced the actress to shed her long, damaged locks for something new. While Aniston only wore the style through Season 3, it was a hit for most of the rest of the decade. Apparently, it was hard to replicate, but McMillan charged just $60 for it, if you could meet him at his salon in LA. Honestly, I preferred Dana Scully’s little bob in The X-Files, but that’s just me. The bob was also popular on stars like Victoria "Posh Spice" Beckham and Cameron Diaz. One last iconic hair moment? Demi Moore shaved her head bald for her role in 1997’s G.I. Jane.

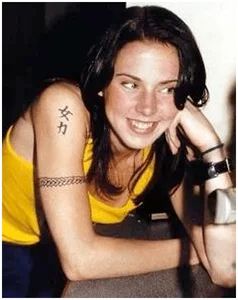

Tattoos Became Common

It may be hard to imagine, but before the 1990s, tattoos really weren’t that common or accepted. They were still stigmatized during the era, but they were increasingly legal and showing up in the mainstream. In New York, tattoo parlors popped up after tattooing became legal in 1997. Shops had been mostly underground since being banned in 1961. By 1996, over half of the people getting tattoos in America were women, who got everything from butterflies to hearts to roses to stars to all the Tweety Birds I saw growing up. Random words in Japanese and Chinese were also trendy. Permanent makeup was also on the menu.

Other popular tattoo trends included tribal designs, popularized by Filipino American artist Leo Zulueta, who inked numerous tastemakers including Dennis Rodman and Tommie Lee. His contemporary designs spread like wildfire, especially because the proliferation of the Internet meant tattoos were no longer localized. The appropriation of such sacred cultural art was lost on people in the nineties.

Famous tattoo included Tupac’s THUG LIFE stomach tattoo, which he received at Dago’s Tattoo in Houston in 1992. Pamela Anderson got her highly visible barbed wire tattoo because she didn’t feel like sitting through daily makeup while filming the title role in the 1996 film Barb Wire. Lastly, tattoo removal technology improved in this decade, with Cher successfully starting the process to remove pieces of ink she had received in the seventies. She said in 1999, "I had my first tattoo at 27, and at that time it was a statement," she said. "Now, just about everyone has one, and it's boring.”

Comments