6 True Crime Stories From The 1990s

- Elexus Jionde

- 4 days ago

- 24 min read

From the Menendez Brothers and O.J. Simpson trials dominating CourtTV (launched in 1991) to shows like Forensic Files and the indulgent documentaries on cable networks, true crime was sensationalized and consumed at unprecedented levels in the 1990s. The ways these crimes were covered, interpreted, and responded to also spoke volumes about American culture, anxieties, and politics. Here's six True Crime stories from the 1990s that impacted society.

1990: The Isabella Stewart Gardner Art Museum Heist

In Boston, Massachusetts, the St. Patrick’s Day celebrations were still in full swing in the early hours of March 18. Two guards, 23-year-old Ricky Abath and 25-year-old Randy Hestand, were clocked in for $6.85 an hour at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum of Art. It was Hestand’s first day on the job, and aside from a few fire and smoke detectors going off for no apparent reason earlier in the evening, the night had gone pretty smoothly.

The museum had opened in 1903 to showcase the art collection of millionaire Isabella Stewart Gardner and her late husband. There were approximately 16,000 pieces sourced from around the world during their travels, including 3,000 rare books and 7,500 paintings, such as The Story of Lucretia by Botticelli. Gardner died in 1924. In her will, she specified that the museum’s holdings couldn’t be rearranged, sold, or significantly added to, otherwise, the property would transfer to Harvard.

By the eighties, endowment funds were running low, so the museum was not only strapped for cash but also suffering from severely outdated security infrastructure. There were no cameras inside. Guards could only summon police by pressing a lone button at the front desk, and unlike at other museums, there were no required hourly check-ins with law enforcement. Instead, guards were only required to make solo rounds each hour, as infrared motion sensors recorded their movements. As one guard walked, the second guard remained at the desk with his walkie-talkie, ready to press the emergency button if need be.

Amid St. Patrick’s Day revelry, a few partygoers later reported seeing two police officers outside the building at 12:30 AM. Inside the museum, sometime after midnight, Abath briefly opened a side entrance and quickly shut it. He then switched duties with Hestand at 1:00 a.m. Shortly before 1:24 a.m., two men dressed as police officers sought entry into the building through a side entrance monitored by a surveillance camera, claiming they were investigating a disturbance. Abath, a former student at Berklee College of Music, who would later admit he sometimes came to work drunk or high (though not on this night, he insisted), buzzed them in.

According to Abath, the fake officers asked him to provide identification. When he stepped out from behind the desk to hand it over, one of them said, “This is a robbery,” and handcuffed him. When Hestand returned to the desk, he too was handcuffed. Now, neither guard had access to the emergency button. The intruders blinded both guards with duct tape and led them to the basement, navigating there without hesitation, suggesting they already knew the layout.

Approximately 24 to 26 minutes after entering, the thieves ascended the main staircase into the museum and began carefully stealing 12 works of art from the Dutch Room and the Short Gallery, trimming several paintings directly from their frames. Among the stolen pieces were Rembrandt’s only known seascape, The Storm on the Sea of Galilee; his painting A Lady and Gentleman in Black; and The Concert, one of only 34 known paintings by Johannes Vermeer. The Storm on the Sea of Galilee had been hung on a false wall that doubled as a door, but the thieves simply opened it, furthering police suspicions that this was an inside job. They also took a few lesser-valued items and unsuccessfully tried to remove a Napoleonic flag, ultimately taking the gilded eagle statue attached to it instead.

Their total haul was estimated to be worth between $200 million and $600 million at the time. Meanwhile, far more valuable works, such as The Rape of Europa, a 16th-century painting by Titian, were left untouched. While most art robberies, and robberies in general, are brief, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist was a puzzling 81 minutes. The thieves could have stolen more, and better-valued, art, but they didn’t. Remember how I mentioned they stole 12 pieces from two rooms? A thirteenth piece, a small Manet called Chez Tortoni, was taken from the Blue Room, which the museum’s infrared sensors never recorded anyone entering, except Abath, earlier in the night. Like the others, it had been cut from its frame, but its empty frame had been left at the front desk.

That’s suspicious. That’s weird.

The thieves took the videotapes from the surveillance camera at the entrance and finally left at 2:45 a.m. The guards were found tied up in the basement later that morning. Police developed two overlapping theories: that Ricky Abath was involved, and/or the Irish Mafia had orchestrated the heist. For starters, the faux cops reportedly called the guards “mates” when putting them in the basement, an Irish slang term. Secondly, the fire detector alarms going off earlier in the evening resembled a tactic commonly used by the Irish Provisional Army overseas. Mob boss Whitey Bulger, who had connections within law enforcement and access to police uniforms, also had ties to the IRA. Multiple Boston Mafia leads were pursued.

But no suspects were arrested. The empty frames where the stolen paintings once hung remain on display, a silent reminder of the most infamous unsolved art theft in U.S. history. In 1994, the museum’s director received a letter from someone claiming to be a third-party mediator, offering to attempt to return the stolen art. The writer claimed the pieces were being kept safe in a “non-common law country” and advised the museum to print a coded message in The Boston Globe if they wanted to proceed. The museum director contacted the Federal Bureau of Investigation, who determined that the writer knew pertinent details only someone close to the case would know. So, The Boston Globe printed a coded message on May 1, 1994.

Within days, a second letter arrived at the museum. This time, the writer seemed nervous and backed out of the proposed arrangement. No further letters came. A $10 million reward issued by the museum didn’t lead to any results. Fast forward to 2013, long after the statute of limitations had expired. The FBI announced that it believed “the art was transported to Connecticut and the Philadelphia region, and some of the art was taken to Philadelphia, where it was offered for sale…”

In August 2015, the FBI released surveillance footage of a car matching the description of the thieves’ vehicle parked outside the museum exactly 24 hours before the robbery. And guess who the driver was speaking to? You guessed it, Ricky Abath. He claimed not to remember the interaction. It was later revealed that the man in the footage was the museum’s deputy director of security. Abath died in 2024. Shortly after the footage was released, the FBI announced they believed they knew who the thieves were: two low-level mob associates, both deceased. Their identities weren’t revealed, likely in an attempt to preserve leads or negotiations to recover the lost artwork, which has still never resurfaced.

1992: The Murder of Shanda Sharer

12-year-old Shanda Sharer was born in Kentucky. A child of divorce, her mom Jacqueline Vaught had remarried and moved twice before they settled down in New Albany, Indiana in 1991. At Hazelwood Middle School, she met 15-year-old Amanda Hearvin during a fight, but the two quickly became romantic. Amanda had an ex-girlfriend named Melinda Loveless, who was fifteen when the pair dated two years before. Melinda was furious and jealous.

Melinda’s last name was truly apt, as she grew up in a loveless, physically and sexually abusive household under parents Larry and Marjorie. Larry was a Vietnam war veteran who allegedly wore his wife and daughters’ underwear and makeup, raped Marjorie, molested his daughters and nieces on several occasions, and forced Marjorie into swinging with other couples. He also had Marjorie gang raped. Marjorie tried killing herself twice. Larry eventually filed for divorce and moved to Florida.

This was the home life of 16-year-old Melinda Loveless, who began hanging out with a 17-year-old lesbian named Laurie Tackett, who grew up in an abusive Pentecostalist household and was rumored to be a devil worshipper. Melinda confronted Shanda in October 1991 and began making public threats to kill her. That same month, Jacqueline found sexual letters from 15-year-old Amanda to her 12-year-old daughter. She transferred Shanda to the private parochial school Our Lady of Perpetual Help. Shanda was banned from seeing Amanda. She got acclimated to her new school, even joining the basketball team. Later witnesses would claim that despite this, Shanda had already begun drinking, smoking “pot”, and “having lesbian sex.”

On January 10th, 1992, Tackett invited her two friends, 15-year-olds Hope Rippey and Toni Lawerence, to accompany her and Loveless to go ‘scare’ Shanda. The girls agreed, and were soon told by Tackett and Loveless that they planned to murder Shanda. They piled into Laurie’s Chevy and drove to Shanda’s father Stephen’s house. Hope and Toni tried to lure her outside, saying her forbidden love Amanda wanted to see her. Shanda told them to come back after midnight when her father was asleep, so the girls left, went to a concert, and came back. When Shanda went out to the car, she was surprised by Melinda Loveless, who subdued her. They transported the 12-year-old to a nearby stone structure ruin called The Witches Castle and tied up Shanda with rope before questioning her about her relationship with Amanda and taunting her.

With Shanda in the trunk, they drove around to multiple locations before taking her to an abandoned area to strip her naked, beat her, and kill her, but their attempts to strangle and stab her only left her unconscious. They threw her back in the trunk. When they went to Tackett’s house to clean off, they heard her screaming in the car, so Tackett grabbed a kitchen knife, went outside, and stabbed her again. Tackett and Loveless then left the other girls behind to drive around with Shanda, who was still clinging to life. Hearing her struggle to breathe, they pulled over so Laurie could beat her with a tire iron. She also sexually assaulted the girl, who was unbelievably still alive. Later that morning, they burned Shanda alive in a field in Madison and then went out for breakfast at McDonald’s, while Shanda’s father realized she was missing and informed the police.

All four of the perpetrators told people what they had done, including friends and the aforementioned Amanda Hearvin. Lawrence and Rippey confessed to police by 8 p.m. that evening, and Laurie and Melinda were arrested the next day. In the process of untangling how such a horrific crime came to be perpetrated by four teenage girls, their backgrounds became pertinent. All of them had engaged in self-harm and/or had been sexually abused. Said Jacqueline Vaught later, “These girls were not born murderers. Something made them capable of this.”

Locals were disturbed. Reported Bob Lewis for The Los Angeles Times, “The case… has unsettled Madison, a picturesque town of antique shops, cozy bed-and-breakfasts and 19th-Century houses nestled along the Ohio River.” Richard Grant blamed small town boredom, describing Madison thusly:

"The problem with Madison is the problem with any small town. There is nothing to do. Life is a constant battle against boredom, in which alcohol and cannabis are the most dependable allies. Otherwise, one can have sex in cars, drive at high speed along the winding country back roads, or, for an added thrill, drive drunk at high speed…The girls make frequent trips to the Louisville shopping malls, for a blissful afternoon of air-conditioned stores and free make-up samples at the beauty counter. Almost without exception, the girls wear heavy make-up, and have permed, teased and frosted hairstyles. Eighty per cent of them are fiercely blonde. They marry young and divorce young. They dream about escaping from Madison, but seldom make it past Louisville…Their horizons extend 80 kilometers south to Louisville, 160 kilometers north to Indianapolis, and 80 kilometers east to Cincinnati, Ohio. Beyond that, the world is televised."

The boring, slow, and traditional pace of Madison made residents indignant about lesbians and rumors of Laurie Tackett being a devil worshipper. That was big city stuff. Said an elderly resident to Richard Grant, “If that poor young girl had been killed in New York, instead of Madison, Indiana, none of you fellows would have batted an eyelid. We’ve got a nice little town here, and I think it’s a shame that it takes something like this to get us noticed.”

All four of Shanda’s murderers were charged as adults and accepted plea deals. Toni Lawrence got twenty years and was released in 2000. Hope Rippey got thirty-five years and was released in 2006. Laurie got sixty years and was released in 2018. Melinda Loveless was given sixty years too. They were also sued by Shanda’s parents to stop them from receiving potential profits from film executives who sniffed around for rights to the story.

When Larry Loveless was exposed during Melinda’s trial for his crimes against his wife and daughters, he spent two years awaiting trial for one charge of sexual battery that wasn’t protected by the statute of limitations. He was found guilty but released for time served. In 2012 Jacqueline Vaught donated a dog to the imprisoned Melinda Loveless to train for the Indiana program that gives service pets to people with disabilities, saying Shanda would have supported it. Loveless was released from prison in 2019.

1993: Lorena and John Wayne Bobbitt

Twenty-three-year-old Marine John Wayne Bobbitt and twenty-year-old Lorena Gallo married in June 1989, after gentle and romantic courting in Manassas, Virginia. Lorena was an Ecuadorian immigrant who had long wanted to move to America and achieve her version of the American dream: marriage. After they tied the knot, the couple moved into a big house, and Lorena alleged the physical, emotional, and financial abuse started. Police responded to multiple domestic violence complaints, and by 1993, John, now working as a bouncer after cycling through roughly a dozen jobs, was taking his wife’s earnings as a manicurist. This was especially tough for Lorena, as she depended on him for her citizenship status. On June 23, he came home, raped Lorena, and fell asleep.

Lorena claimed that she had a psychotic break when she went into the kitchen to get a glass of water after the rape. Snatching up an 8-inch carving knife, she went back into the bedroom and sliced off Bobbitt’s penis. She fled in her car with no shoes, tossing the penis into a field adjacent to a 7-Eleven. She called police and told them what she had done and where to find the penis. Police were dispatched to locate it so it could be reattached in time. When they found it, no joke, they put it in a hot dog box from 7-Eleven. The surgery to reattach the penis was successful and took nine and a half hours. Lorena was charged with assault, facing twenty years, and John Wayne was charged with marital sexual assault in a case that became a major story.

In 1996, Linda Pershing explored the folklore and commentary that emerged in the months and years following the Bobbitt case making headlines. She documented women dressing as Lorena for Halloween, a short sandwich at a local restaurant christened the Bobbitt, and vendors selling buttons outside of the Manassas courthouse that read “Lorena Bobbitt for Surgeon General.” In some Miami coffee shops, patrons asked for “Lorenas,” or black coffee with a little milk. Novelty stores offered Bobbitt Penis Protectors for sleeping men. Chain emails joked to recipients: “What did John Bobbitt say when he was propositioned by a hooker? Answer: Sorry, I'm a little short this week.”

From the name John Wayne Bobbitt, to the hot dog box, to the fact that Lorena’s maiden name was Gallo, which means cock in Spanish, the jokes seemed to write themselves. The fact that witnesses for both John and Lorena affirmed he was physically and financially abusive diminished some of the public sympathy previously given to him.

According to Pershing’s analysis, approximately 1,300,000 column inches had been devoted to the Bobbitts. Underneath the torrent of near-constant CourtTV coverage, TV show jokes, stand-up routines, columns, and email jokes were anxieties about the so-called gender wars, feminism, abuse, and marital rape. Women who supported Lorena emphasized that they understood why she did it, citing their own rapes, abuse, and trauma. Interestingly, most of Lorena’s strongest supporters were fellow Latinas and, more often than not, working class.

Feminists argued over whether or not Lorena was worthy of support, with middle- and upper-class white women leading the attack on what they considered to be “victim feminism.” Argued Susan Estrich, “Lorena Bobbitt is a criminal, not a feminist heroine. Those feminists who have flocked to her defense have done a disservice not only to the cause of feminism, but more important, to the real victims of battered wives' syndrome, the millions of women who are beaten by their husbands and do not respond by assaults on their organs.”

The penis had also become a public spectacle, a word in everyday conversation and news broadcasts. The tale was an uneasy revenge story that some men, laden with guilt for whatever reasons, had to contend with. When Lorena Bobbitt was found not guilty of assault by reason of insanity, the verdict pissed off more than a few men. "In the battle of the sexes, this was like stealing the other team's mascot. This is the result of feminists teaching women that men are natural oppressors,” said the director of a Brooklyn men's rights group. At the time, marital rape was nearly impossible to prove in Virginia. Crowed shock jock Howard Stern, who held a fundraiser to help pay John Bobbitt's mounting legal bills, “I don’t even buy that he was raping her. She’s not that great looking.”

John, who essentially became a sympathetic hero and joke for men who may have raped or abused before, was acquitted of marital rape. The couple’s divorce was finalized in 1995. Lorena reverted to her maiden name of Gallo and continued to live in Manassas, Virginia, despite being a local celebrity and, to some, a boogeyman. She turned down $1 million to pose for Playboy and infamously visited Ecuador to a hero’s welcome, where she met with President Abdalá Bucaram in October 1996. Together, they baptized a child as someone’s godparents. She was later arrested for assaulting her mother in 1997, before being acquitted.

John, meanwhile, went on to make appearances at hot dog eating contests and starred in John Wayne Bobbitt: Uncut, which became the best-selling porn release of 1995. He said he wanted to show people his penis still worked. At one hot dog eating contest at The Abbet Road Grill in 1993, reported The Palm Beach Post, “[Said the announcer]: Ladies and gentlemen, let’s have a warm welcome for John Wayne Bobbitt!” The warm welcome is tepid at best. Most diners don’t even bother to put down their burgers and look up, and those who do squint wincingly into the blazing TV lights, none with a more pained and awkward expression than John Wayne Bobbitt himself.” Bobbitt’s surreal career continued with Frankenpenis, and a trail of domestic violence, battery, and theft arrests followed him through the decade and beyond.

1994: The Assault of Nancy Kerrigan

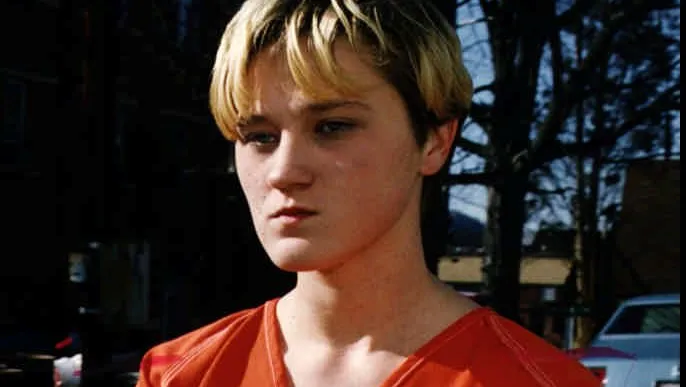

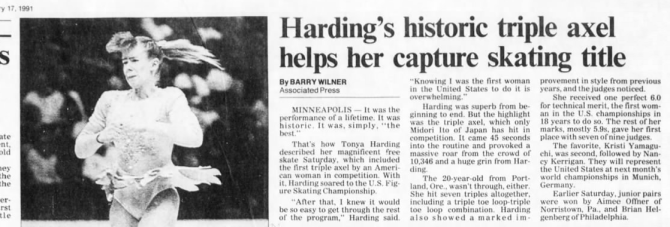

Tonya Harding grew up poor near Portland, Oregon. In addition to hunting and other outdoor activities, she trained as an ice skater throughout her youth while managing asthma. Her mother, who was abusive, spent most of her wages on the competitive skating circuit, which was dominated by the predominantly middle-to-upper class. After years of disappointing scores, Harding had a breakthrough in February 1991 at age twenty during the U.S. Championships, when she landed the near-impossible triple axel. The move was so difficult that she became the first American woman, and only the second woman in the world, to land it in competition.

At the World Championships the following month, she landed another triple axel and won silver, finishing second to Kristi Yamaguchi. Twenty-one-year-old Nancy Kerrigan, from Massachusetts, placed third, making it a full American sweep. Though Kerrigan came from a similarly working-class background, she embodied the refined, WASP-y image favored by the figure skating world. While this would be Tonya’s last successful triple axel in Olympics competition, and she would never again match those scores, she was, for the time being, shaking up the sport with her rough edges and homemade costumes. She attracted a fan base.

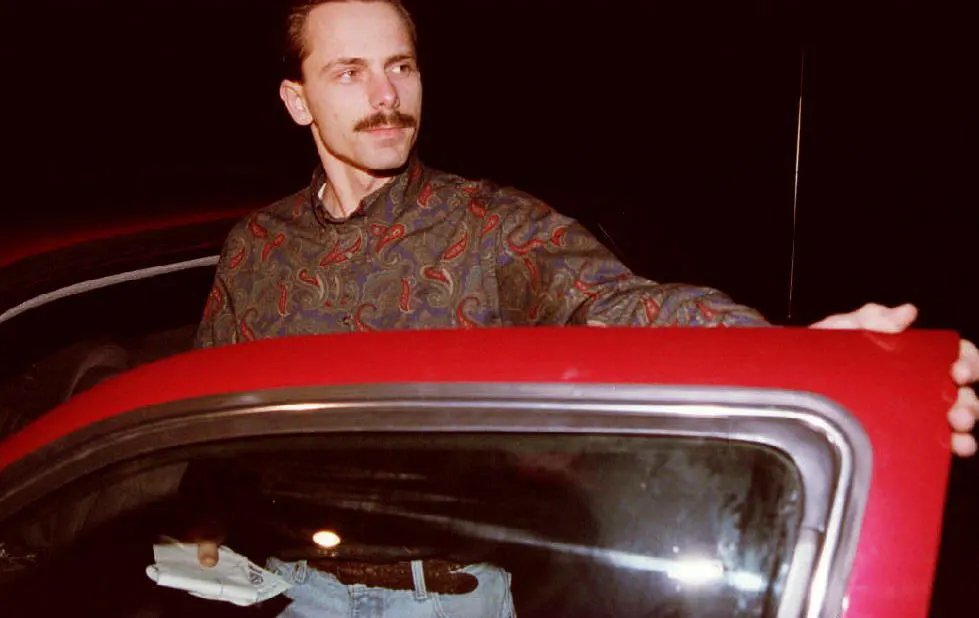

In her personal life, Tonya was married to an abusive man named Jeff Gillooly, whom she had been dating since 1986 and living with on and off since 1988. He helped pay for her skating expenses. Tonya’s career was lackluster in 1992, the same year she was involved in a road rage incident, during which she allegedly threatened someone with a bat. According to police and media, it was a baseball bat; according to Tonya, it was a wiffle bat. Commentators noted that she was out of shape and no longer performing the triple axel. Her coach explained to the Chicago Tribune, “A lot of the behavior she had and statements she made were because she thought her privacy was invaded.” The writer added, “That may no longer be a problem… the way she is skating…”

In 1993, Tonya began to train more seriously. She still had support. Tonya Fever had swept Oregon, and a fan club was established in her honor. Susan Orlean described the group as “suggesting additional opportunities to support Tonya… fundraising… giving her cosmetics, hair care, and nail care… making calls about her to sports talk programs, or… mailing her encouraging cards.” Tonya’s main rival for the upcoming January 1994 nationals was Nancy Kerrigan, the reigning 1993 champion. Tonya hoped to channel her energy into unseating Nancy, but her personal life continued to unravel.

She and Jeff planned to divorce a second time, though they’d be back together by October. That same month, it was reported that Tonya allegedly fired a gun during a domestic dispute. In November, Tonya received a threatening phone call that caused her to withdraw from a competition. Jeff Gillooly’s friend, Shawn Eckardt, a braggadocios compulsive liar, became her bodyguard and would later claim that Tonya hired him to make the threat herself.

On January 6, 1994, Nancy Kerrigan was practicing at the Detroit Cobo Arena when an assailant named Shane Stant, who had followed her from Cape Cod to Detroit, struck her leg with a 21-inch baton. A cameraman filmed Nancy crying out in pain, sobbing “Why?”

Stant fled toward a set of locked doors, threw himself headfirst through a sheet of plexiglass, and jumped into a getaway car driven by his uncle, Derrick Smith. Nancy’s leg was bruised, forcing her to withdraw from the upcoming competition. Immediate suspicion fell on Tonya Harding, who won the U.S. Championship title on January 8, securing her spot on the 1994 Olympic team. On January 10, when asked if someone she knew had planned the attack, Tonya replied, “I have definitely thought about it.”

The incident became an immediate media sensation, with figure skating thrust into the national spotlight. Reporters descended on sleepy Portland, and thousands came to watch Tonya practice at her usual ice rink in Clackamas Town Center. Reported The Washington Post, “This quaint, mellow city of parks, coffee houses and microbreweries sitting in the shadow of Mt. Hood has largely been divided between Harding supporters and detractors. But a new, bigger group has emerged: those who are sick and tired of this sensational soap opera.”

Some locals welcomed the economic boost. Added The New York Times, “One eatery… hung a 28-square-foot sign outside its doors that reads ‘Lila’s Tonya Special: A Club Sandwich and Chicken Soup.’” Many were inspired to join the Tonya Harding Fan Club and support the working-class Harding for $10. One member told Susan Orlean after the scandal, “Scum. That’s what they call us. It’s a class difference, that’s what all this mess is about, Tonya. She’s just a regular Clackamas County girl. In my opinion, she’s a modern gal, what we would call a tomboy. She can hunt, she can fix a car. She calls herself the Charles Barkley of figure skating, and she’s right. She’s a stud.”

Orlean wrote, “The Tonya Harding Fan Club, which was started a year ago, has seen its ranks almost double to around 800 members from 32 states and seven countries, including Australia and South Africa.” While Tonya publicly denied knowing anything, Shawn Eckardt bragged to nearly everyone that he had orchestrated the attack on Nancy, and even his own father joined in the boasting. Eckardt, Shane Stant, and Derrick Smith were arrested by January 13, thanks to their lack of discretion and a series of foolish mistakes. The men implicated Tonya, claiming she had been involved in the plan.

Tonya again denied any prior knowledge through her lawyer three days later. On January 18, she told the FBI in a ten-and-a-half-hour interview that she only learned of the plan after January 11. Jeff Gillooly began cooperating with the FBI on January 26, telling agents that he and Tonya discussed mailing threatening letters to Kerrigan. He also claimed she seemed interested in a plan to physically harm Nancy.

The next day, Tonya announced at a press conference that she had learned Jeff plotted to harm Nancy. On February 1, the day after Nike pledged $25,000 to sponsor Harding in the Olympics, the owner of a Portland restaurant called the Dockside Saloon discovered discarded garbage in her private trash cans. Searching through it out of spite so she could send the garbage back to the owner, she found a check stub made out to Tonya and a piece of paper in Tonya’s handwriting detailing Nancy Kerrigan’s practice venue in Detroit and her training schedule. The handwriting was later matched to Tonya’s after the restaurant owner, Peterson, contacted the FBI.

Jeff Gillooly secured a plea deal to serve two years in exchange for testifying against the others. Shawn Eckardt pleaded guilty to racketeering and received 18 months but was released 109 days early. Shane Stant and Derrick Smith pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit assault and each received 18-month sentences, Stant served only 14.

On February 5, the U.S. Figure Skating Association gave Tonya 30 days to respond to allegations of misconduct, while the U.S. Olympic Committee prepared to remove her from the team and replace her with Michelle Kwan for the 1994 Winter Olympics in Norway later that month. Tonya filed a lawsuit on February 10, but two days later, she was officially allowed to skate. Michelle Kwan was sidelined, for now, but she would bounce back by the end of the decade to become one of the most iconic names in figure skating, if not the most iconic. The Olympics leaned into the Harding vs. Kerrigan drama, and the world watched eagerly to see them face off. The event’s ratings surpassed the Super Bowl, becoming the third most-watched televised event in history at the time.

On February 25, Kerrigan earned the silver medal. Tonya, after breaking a bootlace and pleading to restart her lackluster performance, ultimately finished in eighth place. The next month, Tonya pled guilty to conspiracy to hinder prosecution, admitting that she had learned about the attack after it was committed and helped Shawn and Jeff come up with a cover story on January 10. She received three years of probation, a $100,000 fine, fifty hours of community service, and a lifetime ban from the U.S. Figure Skating Association. She was also stripped of the U.S. Championship title she had won that January. Jeff Gillooly, whose name, and mustache, had become a national punchline, leaked photos from their wedding night sex tape to Penthouse Magazine and Hard Copy in August. Tonya received a cut of the profits when Penthouse sold the tape. By October, the remaining loyalists in her fan club disbanded.

The case became a defining piece of cultural lore in the 1990s, touching on class, gender, and media spectacle. Tonya came to represent the "white trash" stereotype that the national media increasingly obsessed over, and if not for her ability to land the triple axel, she likely would have remained shut out from the skating world altogether. Mused Jill Smolowe for Time,

“Tonya Harding is not, nor has she ever been, like most skaters. She is neither politic nor polished, sociable nor sophisticated. Instead, she is the bead of raw sweat in a field of dainty perspirers; the asthmatic who heaves uncontrollably while others pant prettily; the pool-playing, drag-racing, trash-talking bad girl of a sport that thrives on illusion and Nationalism, Whiteness and Tonya Harding politesse. When rivals fairly float through their programs, she’s the skater who best bullies gravity. She fights it off like a mugger; stroking the ice hard, pushing it away the same way she brushes off fans who pester her for autographs.”

Tonya’s anger issues and involvement in the attack swept her into a pop culture category alongside other infamous women of the decade. One 1994 chain email joked: “I dreamt that I went to bed with Hillary Clinton, Lorena Bobbitt, and Tonya Harding. When I woke up this morning, my knee was killing me, my manhood was gone, and I didn't have any health insurance.” As the nonstop coverage and punchlines faded, Tonya sporadically popped up to capitalize on her celebrity by taking on odd jobs, including being hired as a skater at hockey games, where she was often booed. She performed well in the ESPN Professional Skating Championships in 1999, but her skating career never rebounded. Eventually, she transitioned into boxing, even fighting Paula Jones in 2002. Tonya won by technical knockout when Paula quit.

Nancy Kerrigan briefly continued her skating career. While she received widespread sympathy from the public and media leading up to and during the Winter Olympics, the tone shifted afterward. When Nancy was overheard saying, “This is so dumb. I hate this,” during a visit to Disney World, a comment taken out of context, she was labeled as ungrateful and bitchy. Remarked Ira Berkow for The New York Times, “So now you hear how people have gotten nauseous from Kerrigan’s smile, ‘too many teeth’, and her girlish voice, which they perceive as masking something darker within her heart.”

1995: Maria Farmer and Jeffrey Epstein

In 1991, Jeffrey Epstein was granted full power of attorney over billionaire Leslie Wexner’s affairs. Wexner, CEO of L Brands, which included The Limited and Victoria’s Secret, was also a major donor to The Ohio State University. By 1995, Epstein was directing multiple Wexner businesses and regularly attending Victoria’s Secret fashion shows. He was in the orbit of many prominent celebrities, business leaders, and politicians. That same year, a 24-year-old artist named Maria Farmer was introduced to Epstein and his companion, Ghislaine Maxwell, by Eileen Guggenheim, Dean of the New York Academy of Art.

Ghislaine was the wealthy daughter of British-Israeli media publisher and fraudster Robert Maxwell. When her father turned up dead (possibly murdered) in 1991, his funeral in Jerusalem was attended by top Israeli figures, including the Prime Minister and President. Ghislaine received a hefty yearly pension from his estate and embarked on a socialite existence in New York with Epstein. By 1992, she was his main confidante and responsible for managing his staff.

Maria Farmer, who painted nudes and figurative pieces exploring girlhood and body acceptance, didn’t think much of the encounter at the time, but Epstein expressed interest in buying her work. It marked the beginning of a series of encounters with the multi-millionaire. Epstein invited her and three other artists to a post-graduate, all-expenses-paid workshop in Santa Fe, New Mexico, for a commission job that ultimately did not exist. He later hired her as an “art advisor” and something akin to a secretary, during which time she witnessed young girls coming and going from his properties at all hours.

By 1996, Epstein had slashed his federal income taxes by 90% by basing his firm in the tax shelters of the U.S. Virgin Islands. That year, Maria was commissioned to paint two pieces for the film As Good As It Gets. To complete the work, Epstein invited her to use Wexner’s guest home in New Albany, Ohio. When Maria arrived in May, she encountered armed security and was informed that she could not leave the property without permission from Abigail Wexner, Leslie’s wife.

While confined to the home for twelve hours, Maria was sexually assaulted by Maxwell and Epstein. Unbeknownst to her, her younger sister Annie, also an artist, had been assaulted by the same pair in a similar setup the previous month in New Mexico. Maria managed to call her art teacher and her father, the latter of whom drove from Kentucky to retrieve her. On August 26, 1996, Maria reported Epstein, Maxwell, and others to the New York Police Department, but neither they nor the FBI acted. The only notation made concerned “artwork theft” by Maxwell and Epstein.

In 2003, while journalist Vicky Ward wrote a profile of Epstein for Vanity Fair, she made some troubling discoveries. Not only did numerous sources reference underage girls, but Maria and Annie Farmer came forward to share their experiences. Ward, who was pregnant at the time, later claimed that Epstein threatened her. Editor-in-Chief Graydon Carter killed the allegations from the final story, which included Epstein calling Ghislaine his “best friend.” Epstein and Maxwell’s tangled web of abuse and privilege only continued to grow more brazen and unchecked.

1997: The Murder of Sherrice Iverson

On May 25 1997 in Primm, Nevada, 7-year-old Sherrice Iverson was left in the care of her 14-year-old brother while their father drank and gambled at Primadonna Resort & Casino. At approximately 3AM, while her brother played video games in an arcade, she was spotted in the casino alone by 18-year-old Jeremy Strohmeyer, who was on vacation with his 17-year-old best friend David Cash and his father.

Strohmeyer followed Sherrice into the women’s restroom, where Cash witnessed Strohmeyer dragging Sherrice into a stall. He exited. In the twenty minutes that Cash could have went to flag down help, Strohmeyer sexually assaulted Sherrice and strangled her. He told Cash, who did nothing. The teenagers went out to other casinos for the next few hours before going home to California. Three days after the murder, Strohmeyer was arrested because he had been caught on the casino cameras.

Strohmeyer immediately confessed and was sentenced to life in prison the following year after pleading guilty to avoid a trial. Reported The Washington Post, “The prosecution contended Strohmeyer is a killer who hoarded pornography and admitted fantasizing about sex with young girls. Strohmeyer's defense, on the other hand, had portrayed the former high school honor student as a troubled youth whose father is in prison and whose biological mother is in a mental hospital…”

The public, and Sherrice’s mother Yolonda Manuel (who lived in California), were outraged to find out that David Cash witnessed the crime and did nothing. Because Nevada did not have a law requiring people witnessing a crime to do something or call law enforcement, he got off without punishment. People demanded a new law. Reported Don Terry, “The uphill campaign has attracted a coalition of supporters rare in this era of polarization: blacks, whites, Jews, Christians, Muslims, radio talk-show hosts, conservatives and liberals.” Said Yolanda, ''This ain't a race issue. This ain't a political issue. It's a human being issue. It's a justice issue for a little girl who will never be able to reach for her goals. My baby won't ever get to go to college.''

In 1998, when Strohmeyer was about to go on trial and Cash was a sophomore at University of California Berkeley studying nuclear engineering, several students protested in an effort to get him expelled. Two former friends came forward alleging that Cash witnessed the sexual assault, not just the kidnapping. Cash was brutally cold in interviews, saying to the Long Beach Press-Telegram, "I’m no idiot. I’ll get my money out of this.” When asked if he felt empathy for Sherrice, he said to The Los Angeles Times, "I’m not going to get upset over somebody else’s life. I just worry about myself first. I’m not going to lose sleep over somebody else’s problems." A year before the Columbine massacre, he represented the apathetic, dangerous, and privileged white sociopath. Described Stephanie Salter,

“He says he feels sorrier for Strohmeyer than for the murdered child - after all, he didn't know her. He once said his newfound notoriety makes it easier to "score with women." He says he just wants to get on with his life, majoring in, of all things, nuclear engineering. He says if he had it to do over again, he'd make the same choices. Each time Cash turns his pale, unexceptional face to the world and does not say, "I'm sorry, I did a horrible thing," the easier he is to hate, the more we want to wash our hands of him. Clearly, this boy-man is not lying or in denial; he does not believe he did wrong.”

A writer and spokesman for the Sherrice Iverson Memorial Bill in California named Earl Ofari Hutchison said, ''We can't deny that race has a role in this case. But the mother doesn't want to bring it in. And that makes sense. After O. J., as soon as you mention race, you've polarized, you've drawn a line in the sand.” In the end, everyone failed Sherrice, including her father, the casino, and Cash. Both California and Nevada passed Good Samaritan legislation making it a crime to not report crimes to the police.